Archive of the Mendocino Heritage Artists

Dorr Bothwell’s Samoa

NOTE: Dorr Bothwell considered the artwork she did in Samoa her finest. From 1928 to 1929 Bothwell produced hundreds of pieces, but our archive has only these few images from that seminal period in her life. If you have other, or better, digital images to share, please contact us. Thank you.

Excerpts FROM “I’LL PRETEND THAT I’M GOING TO ART SCHOOL”: DORR BOTHWELL IN SAMOA, 1928-1929

by Kelly Quinn, Archives of American Art Journal 52, no. 1/2 (SPRING 2013): 70-79. https://doi.org/10.1086/aaa.52.1_2.43155569 [Editor’s notes are in brackets.]

[REVERSALS IN FORTUNE]

…When [Dorr Bothwell’s] family’s fortunes shifted after her father’s unexpected death in 1927 [see Port Gamble], Bothwell was left without funds. She sought then to live cheaply and took odd jobs (waitressing and occasional teaching gigs, for example) but continued to paint and draw. In spring 1928, Bothwell inherited $3,000 from her Auntie Trissie [Bothwell’s Aunt Maria Theresa von Lushcka, who was living in Switzerland at the time of her death], and like generations of artists before and since, the unexpected windfall enabled her to pursue art.

Quite pragmatically, she wanted to stretch the money and decided to avoid “the city” in favor of someplace “simple and primitive.”

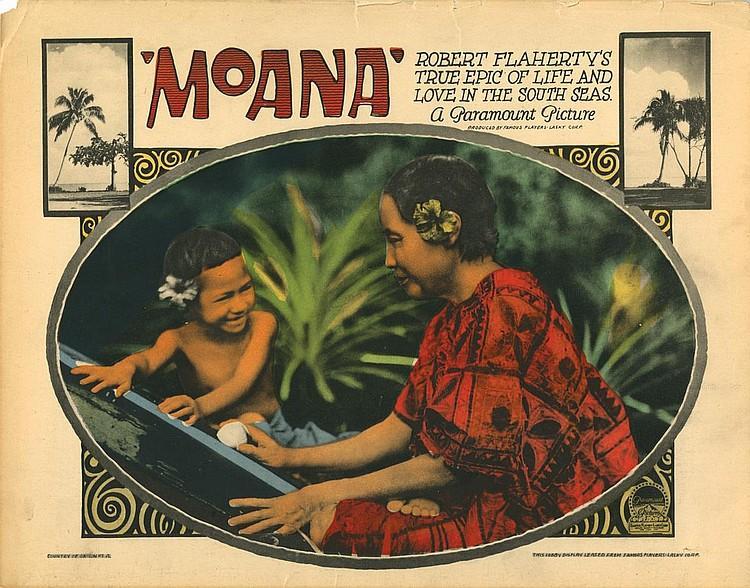

[ROBERT FLAHERTY’S MOANA]

The South Pacific islands had appealed to her after she saw Robert Flaherty’s documentary Moana in early 1926.

Flaherty’s Moana intrigued and inspired Bothwell. She was captivated by the aesthetics of the silent film, and it also served as a moving-picture field guide to the possibilities of life in the South Seas. It depicted a native Samoan community’s preparations for a major celebration: the rite of passage of the young male protagonist, Moana. Flaherty included scenes of native men and women—including elders and children—hunting wild boar; spearfishing; capturing giant turtles and clams; and foraging for taro and nuts. Men danced and cheered for Moana; women prepared custards and breadfruits, and made barkcloth garments for him.

The rite culminated in a painful ritual: Moana, anointed by his maiden lover, Fa’angase, was tattooed during a lengthy ceremony by artists using tiny hammers.

[PREPARING FOR SAMOA]

In 1928—with Samoa as her destination and her legacy in hand—she quit her part-time job as a waitress at Ingersoll Candy Company in San Diego and prepared to sail.

[Bothwell noted] in her diary: I have 11 yds of the finest belgiuim linen canvas + oodles ($35) of paint. All I hope is that living will be cheap enough so that I can stay long enough to get some work done. What I would like is to be adopted by a native family + live with them so that I get the native food, a chance to learn their language + study their songs + dances etc. Divine [undecipherable] governs so I will find my proper place.

Having appropriated a dust-proof, air-tight trunk belonging to her mother’s Chevrolet coupe, on her twenty-sixth birthday [May 3, 1928] Bothwell carried a roll of canvas, stretcher bars, and paints to her second-class cabin aboard the S.S. Sierra and set off for Pago Pago.

In addition to art supplies, she took with her at least three letters of introduction from instructors and art dealers who attested to her success, hailing her as “a serious and recognized artist.”

Her former art teacher Rudolph Schaeffer mentioned Bothwell’s desire to study the traditional Polynesian arts and crafts featured in Flaherty’s film, explaining that Bothwell possessed an interest in “studying the sources of underlying impulses producing individual expression of decorative design with various races in different lands.”

[“ART SCHOOL”]

With her own work in mind as well, Bothwell devised a plan: Had a bright + brilliant idea—think that I’ll pretend that I am going to ‘art school.’ Will fix out a varied schedule—such as drawing 3 times a week in the afternoons from 1–4—Painting all day 3 times a week + in the forenoons that are left over I can either write, sketch or do my laundry, wood blocks, etc.

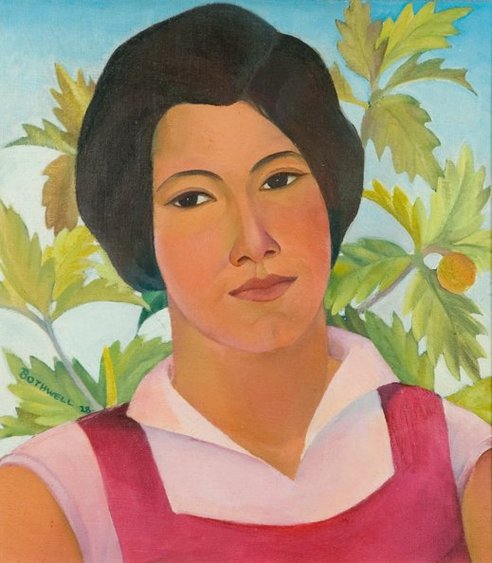

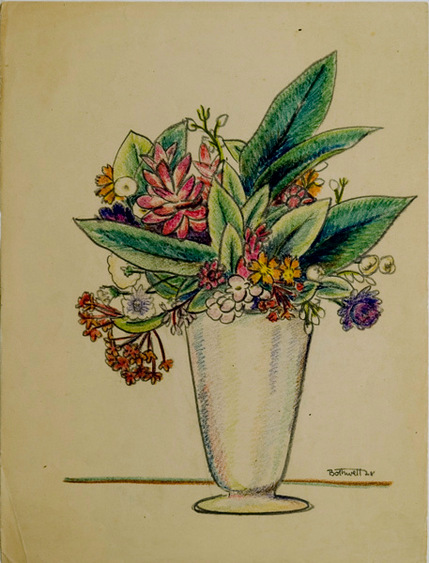

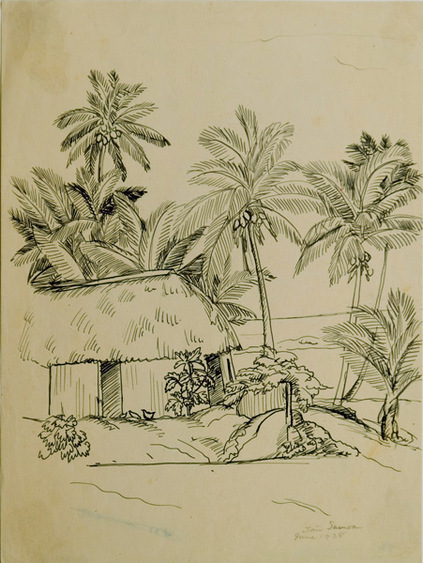

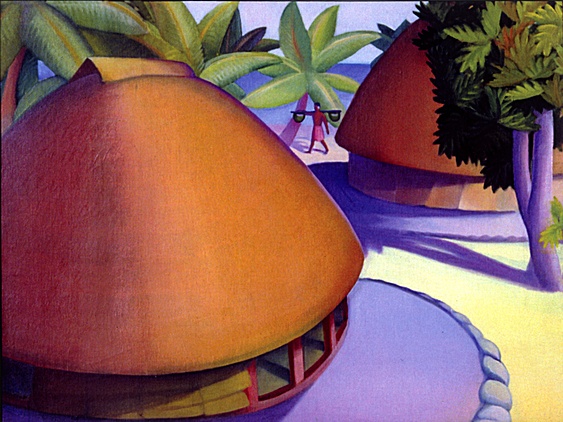

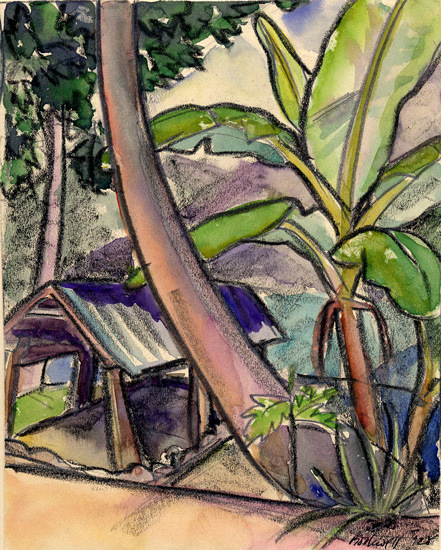

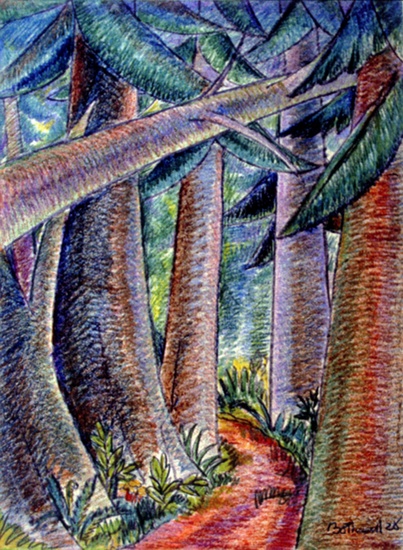

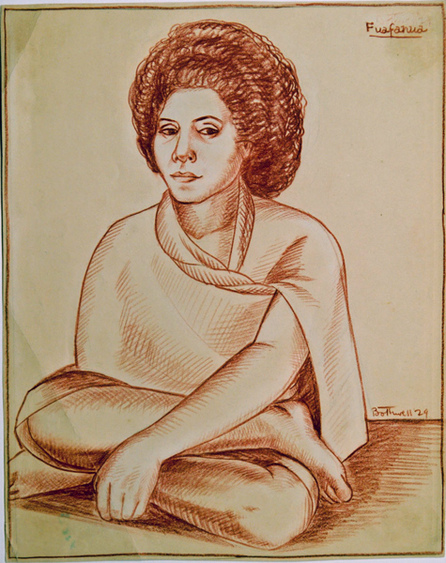

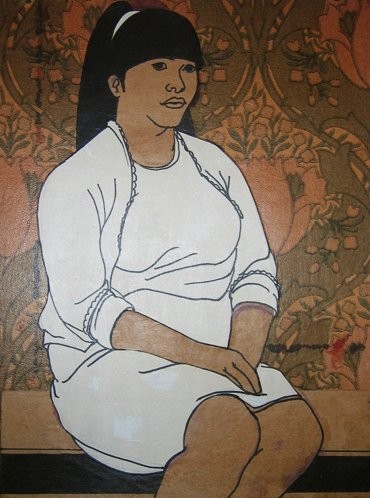

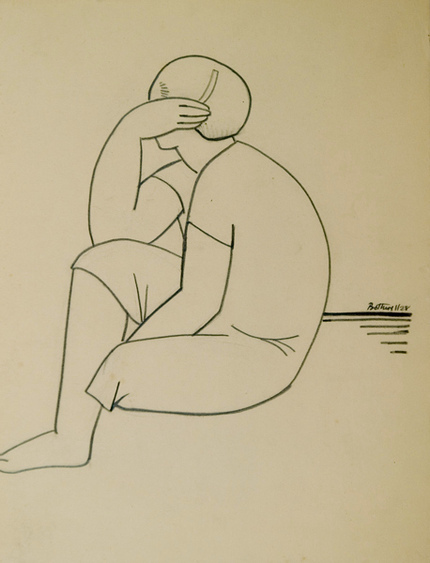

Bothwell was very productive in Samoa, [painting] portraits, landscapes, figure studies, and abstract compositions [and making] numerous studies of everyday life in pen, pencil, crayon, wood-block prints, and watercolor.

Annie by Dorr Bothwell (Samoa 1928). Oil on board. Private collection.[Bothwell] made dozens of studies of botanicals like hibiscus and frangipani as well as portraits of Samoan friends and neighbors. She continued working on several series that she had developed in the United States, including a portrait of her family from 1909, and began new ones.

[PHOTOGRAPHY]

Six months into her stay, she sent to her mother for her camera equipment, and once she received it, she snapped rolls of film and processed and printed images in a makeshift darkroom at a friend’s house.

[RAISING MONEY TO STAY LONGER IN SAMOA]

Remarkably, despite being on a remote island, Bothwell also kept her hand in at home. She entered contests sponsored by magazines like Life and sent pictures through the mail for her mother and San Diego gallery director Reginald Poland to sell. The profits enabled her to extend her stay in the Polynesian archipelago to nearly two years.

[DORR BOTHWELL’S SAMOAN DIARIES]

During her time in the South Pacific, Bothwell recorded activities in a pair of diaries, sharing impressions, reporting gossip, and preserving the personal musings of a single woman in an extended period of self-examination.

Routinely, she noted her experiences dancing, singing, cooking, baking, eating, swimming, gardening, sketching, reading, and praying.

She wrote about her work and efforts to generate money, made notes about the exotic world around her, and marked episodes of ennui, uncertainty, and excitement.

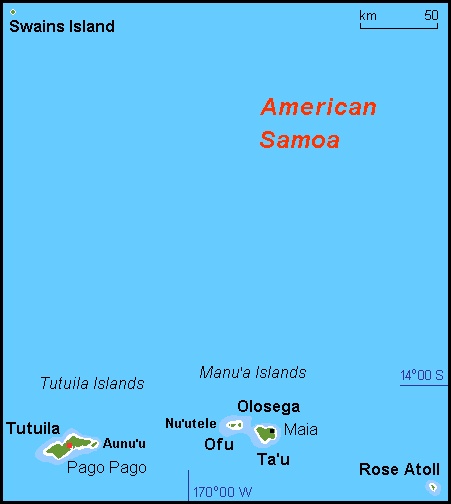

Living on Ta`ū, she immersed herself in the rituals and customs of Samoan culture.

Not surprisingly, Bothwell approached her tenure in the South Pacific as an artist, observing the “visual differences” among native residents and between natives and white people like her…

The Samoans have the loveliest skin—smooth + very fine—especially the young girls + boys. They bathe at least twice a day + then rub oil on, especially at night + I suppose that has something to do with the nice texture their coloring defies analysis. They are all colors—but no matter what shade—light or dark—they are stunning against the green foliage of their jungle like hills. When I think of what a sorry sight two hundred white people—country people or that would be were they asked to wear only a lava-lava—my respect for the Samoan from an artistic standpoint at least, goes soaring up.

[In Samoan Family Resting, the mother and father are wearing lava-lavas, the graceful leisure garments of choice on Ta’u. ]

In some entries, Bothwell described Samoans as exotic figures; in others she detailed the lives of individual men, women, and children.

She was particularly fascinated by Samoan decorative rituals, dances, and material culture. Indeed, within two days of landing on Ta`ū, Bothwell began her study of Samoan women’s traditional handcrafts.

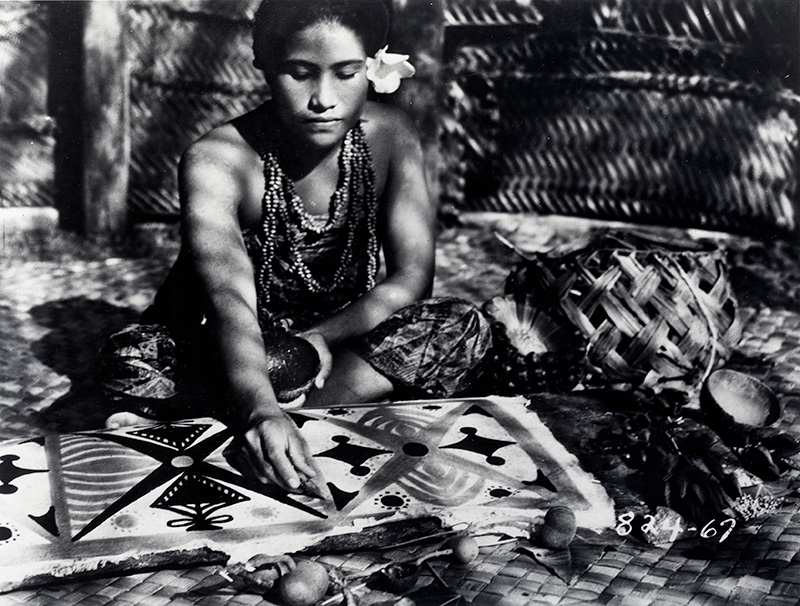

[SIAPO MAMANU]

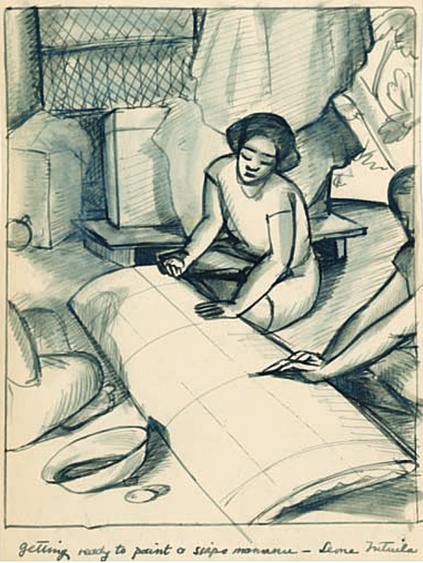

On the morning of May 30, she watched the activity, which first fascinated her in a darkened movie house thousands of miles away, of a woman making [the Polynesian pounded barkcloth generally known as tapa In Samoa, Bothwell learned that the Samoan word for tapa is siapo, and hand painted, rather than block printed, tapa is siapo mamanu.]

Bothwell joined in enthusiastically, as she later explained in her diary, “much to the amusement of about 2 dozen children.” Throughout her daily entries, Bothwell made notes about women and children working with barkcloth.

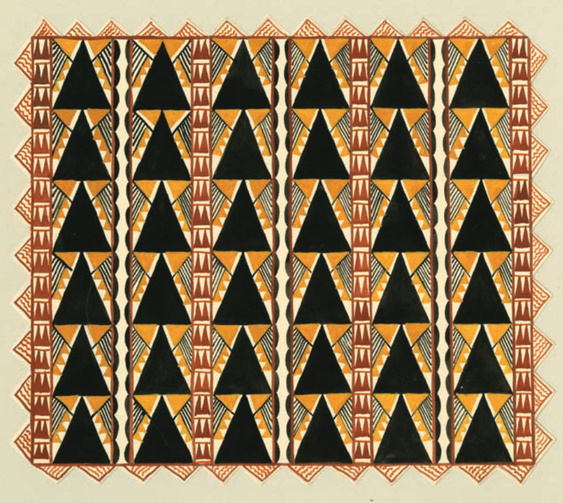

Bothwell investigated siapo preparations, detailing the local women’s work in her sketchbook in colored pencil, crayon, and watercolor. She researched origins, practices, and customs associated with the paper of mulberry bark on the island. The Samoan artists’ rhythmic patterns shared a design vocabulary of the popular Art Deco style that Bothwell would have known in the United States.

[TAPA IDEAS]

By late September 1928, the industrious and frugal Bothwell developed plans to document Samoan siapo and to capitalize on indigenous art both as a commodity and object of expertise.

She noted: Tapa ideas to date are—

Series of articles + plates for Bishop Museum

Collection of 50 tapas to be sold in N.Y. S.F. + L.A.

Collection of tasina patterns printed on muslin for lecture purposes

Sketches of tapa + tasina patterns for teaching

Adaptations of patterns for silks [ for designs to be sent to Cheneys]

Not so hard?

I’ve started the outline of letter to Macy’s describing in detail this phantom collection of 50 tapas. Will type it off + illustrate it tomorrow. Also got my cartoons for Life [Magazine] ready to send. Gee with all these irons in the fire—something should turn up.

…Bothwell compiled an eleven-page ethnological report, typed up her findings, and prepared seventeen measured drawings in Notes on Modern Samoan Siapo, that she submitted to the Bishop Museum, a natural and cultural history museum and archive in Hawaii.

[BECOMING PART OF THE COMMUNITY]

The diaries show how closely involved Bothwell became with Samoans and their culture, to the benefit of her research. Bothwell practiced speaking Samoan, learning vocabulary and vernacular expressions. While she continued to develop her Christian Science faith through reading and work, Bothwell also attended Sunday church services and prayed with local residents.

Soon after her arrival on the island, she gained an important entrée into the community when Chief Sotoa, the local chief, bestowed her with “Soaifetu,” an honorific Samoan name [specifically, “the daughter of the chief“].

[In fact, in late 1928, in order for the American colonial authorities to permit Bothwell, a young white woman, to continue to stay in the village chief’s household, she had to become Samoan. In order to keep her from being deported, the chief invited her to become his daughter, and adopted her.]

[TAKING SAMOA WITH HER]

Perhaps the most dramatic example of Bothwell’s experiences was getting a tattoo “foasamoa.” [“Fa’asamoa” can be defined as “in keeping with Samoan cultural traditions,” but more than that, fa’asamoa is an expression of deep Samoan cultural pride].

Read Dorr Bothwell’s description of her tattooing experience.

Despite his initial surprise on learning that he was to adorn her, the visiting master tattoo artist, a tufuga, hammered patterned bands onto her upper legs during a four-hour session.

[Painful traditional tattoos were part of the adoption process. Bothwell’s tattoos are the kind given only to a chief’s daughter.]

The occasion was not the kind of formal, community-wide ceremony featured in Flaherty’s film, but this unusual and painful process ensured that she wore Samoa for the rest of her life.

[Note: Dorr Bothwell’s tattoo process was not the community-wide ceremony portrayed in Moana, in part because she was a woman, and in part because it was performed away from most of Bothwell’s Samoan community, although local friends were there to support her. The ceremony was performed on the island where Bothwell had been summoned before American colonial authorities at the American Naval Base on Tuituila, the governor of Samoa, Commander Graham, and a Naval judge, Commander Fox, to learn that she was being deported, without being permitted to return to her Samoan home island even to retrieve her artwork or personal effects. It was necessary for her to become Samoan very fast; otherwise, she would be sent away on the next ship. Fortunately, Bothwells’ hosts had status. Sotoa was the head of the Manu’a island group (Ofu, Nu’utele, Olosega, Maia, and Ta’u), and had been the chief counsellor of the last King of Samoa. Sotoa’s wife Toaga was the sister of the last Queen of Samoa. Sotoa and Toaga had already adopted Dorr in their hearts, so he did not hesitate to offer formal adoption as a happy solution to a bad situation. Reference: Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind: An Artist’s Life as Told to Bruce Levene]

SOME OF KELLY QUINN’S NOTES

I would like to thank Adrienne Kaeppler and Jacob Love for sharing their expertise on Samoa.

3 Autobiographical interview, unpaginated typescript, 1997, Dorr Bothwell Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter Bothwell Papers).

5 Autobiographical interview, Bothwell Papers.

6 Dorr Bothwell, diary, April 19, 1928, Bothwell Papers.

8 October 18, 1928, Bothwell Papers.

9 Autobiographical interview, Bothwell Papers.

10 June 14, 1928, Bothwell Papers.

11 Bothwell diary, [October 10, 1928], Bothwell Papers.

12 Dorr Bothwell, “Notes on Modern Samoan Siapo,” n.d. (ca. 1929). Bishop Museum, Hawaii.

13 Bothwell diary, December 5, 1928.

14 Advertisement, June 11, 1930, Bothwell Papers; Display Advertisement, Los Angeles Times, November 28, 1931, A8; Myra Nye, Club Notes, Los Angeles Times, January 24, 1932; “Artist Wins Samoan Hearts: Chief ’s Foster-Daughter Will Lecture,” Los Angeles Times January 5, 1933, A2.

LINKS

Dorr Bothwell: Artwork

Dorr Bothwell in Her Own Words

Barebones Bothwell

Archives of American Art Terms of Use

Contact

Welcome!