To Dorr

To a distant land —

where we met

she went surrendering to Paris’s call

In a fierce river she once plunged

telling “no way” to a log

which desperately tried to drown her

Relating to the universe’s outer edges

she also knows resurrection to be

in color and form

That’s why the Pacific borrows its blues

from her painter’s eye

–Etel Adnan, Lebanese-American poet, essayist, and visual artist

Dorr Bothwell’s personality resonates throughout her world—much like her ‘resonating hugs’ across the telephone lines. In her art I find a wonderment in. . .a curiosity about and an appreciation of places she has been, dreams she recalls and people she has met.

Everything is interesting to her and must be shared with those around her; I enjoy it all when we are together.

She sparkles—especially when she relates the stories inspiring her paintings and graphics. She is young in outlook, in her heart and in her eyes. I treasure every thought, gesture and evidence of her creative spirit. — Tobey Moss

•

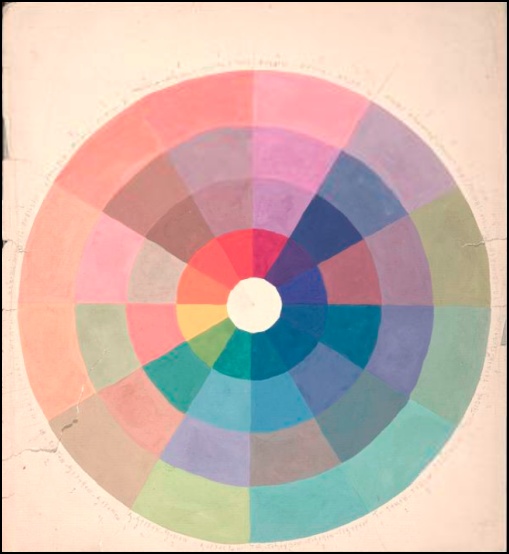

In 1946 I took a course from Dorr Bothwell in Color Theory. I found her one of the most capable teachers I’ve ever known. Her energy, her confidence and her complete dedication to art is incredible. She is a well-rounded person, not just a one-track artist, and has a global interest in everything happening in the world. I found her astonishing as a teacher, one who created enthusiasm among her students.

In later years Dorr and I were members of a faculty team that was invited up to Yosemite to teach at Ansel Adams’ workshop. In a few classes I had the opportunity to work with her, doing criticism of photographs. She’s perfectly at home criticizing photography and related subjects.

It was great to work with Dorr. To me she’s a teacher with no inflated ego about self. There are teachers who have an agenda and can’t put their own personality aside for the good of the student. It’s essential for a good teacher to do that.

Dorr conducted several unique sessions with students in the photography workshop. Quite often they would complain, “Oh, I came here to study photography.” She would seat them, have them relax, even take their shoes off. Then they would begin studying some interesting problems in design that she’d worked out for them.

Words can’t express how I feel about her, both as a person and as an artist. Anybody who studied with Dorr Bothwell experienced something they would never forget. — Pirkle Jones, San Francisco Art Institute

•

In the winter of 1953-54, I had my first treat to Dorr’s sparking personality and enthusiasm for art and artists. On her easel was a magnificent oil, the theme a blue abstract expanse of water. I shall never forget it.

It was Dorr who suggested I come to Mendocino, and to teach the Mendocino Art Center’s first summer session in 1960, “holding the job” for her until she could be in Mendocino the following year. She’s had considerable influence on my life and the art-life of her many students as well. — Hilda Pertha

•

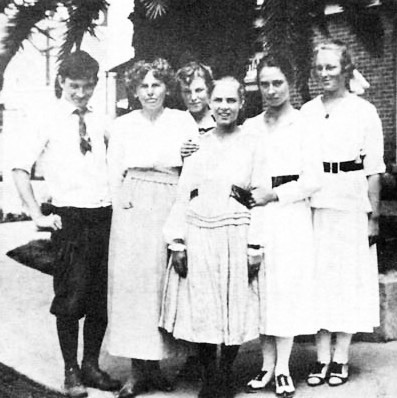

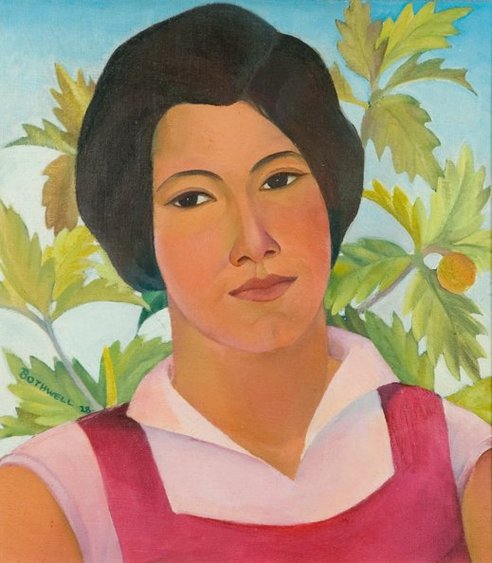

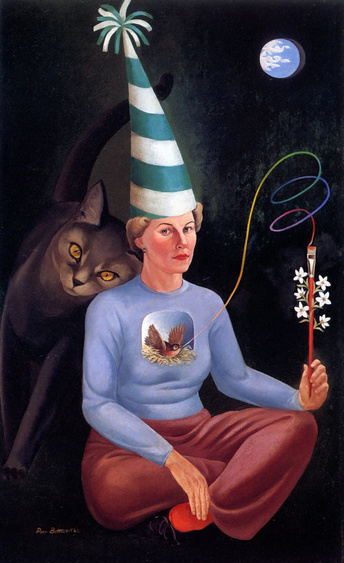

Dorr, a wonderful vital and inspired friend for many years—we met in North Beach San Francisco in 1955—has recently left us. Her life spanned nearly a century from May 3, 1902 to September 24, 2000. She lived with great intensity, sharing herself generously with others, and leaving behind an impressive body of work, which places her among America’s outstanding women artists of the 20th century. — Monica Hannasch, compiler of Dorr Bothwell’s African Sketchbook, 2000

Dorr Bothwell is a woman not afraid to venture into different experiences, who has traveled to various countries, participated in different cultures and experienced different ways of seeing—an artist whose eyes are wide open and ready to experience. An artist of solitude, she values her quiet place, where she sees, where she paints.

Her Quaker background taught her at an early age to commune “within,” to “wait to be told . . . In the writings of great artists you’ll find they always knew that something was painting through them. They were told what to do.”

She feels it is the responsibility of an artist to “silence this know-it-all part of us. Break through the concretion of facts we have collected, to achieve the vision that we had as children and that we must have as artists.”

She sees the artist’s life as “being a different way of life, where the accents are all incredibly different,” centering solely on one’s artwork. — Valliere T. Richard

•

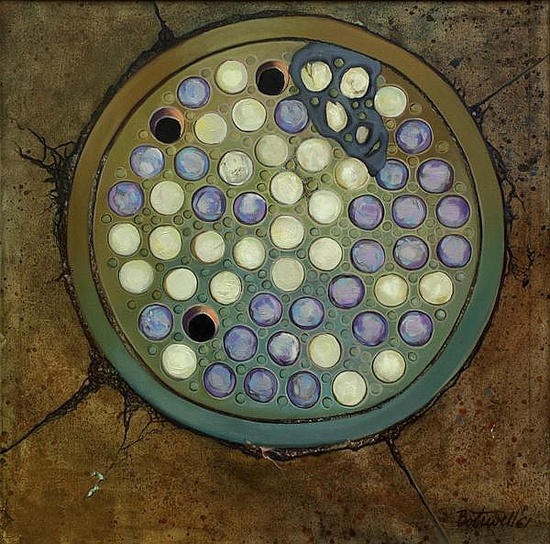

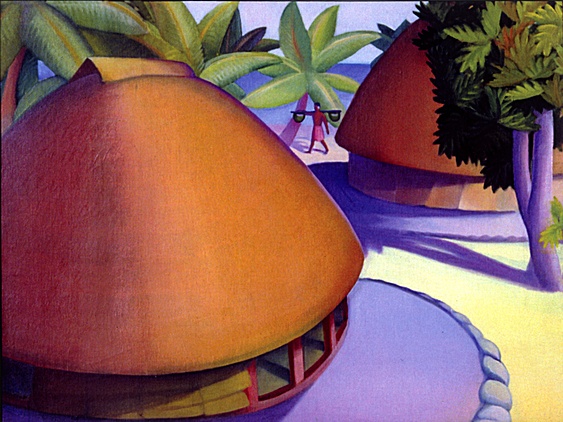

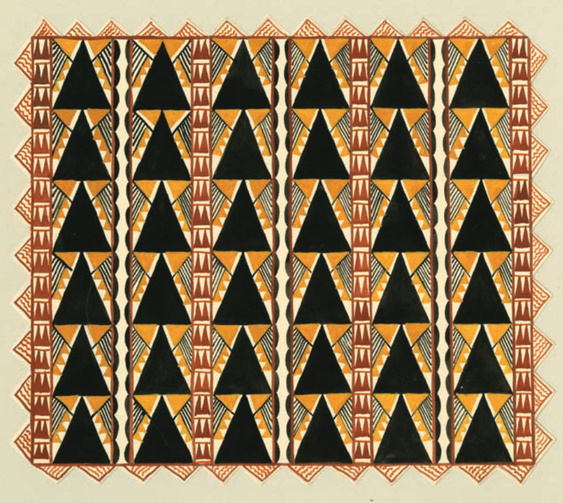

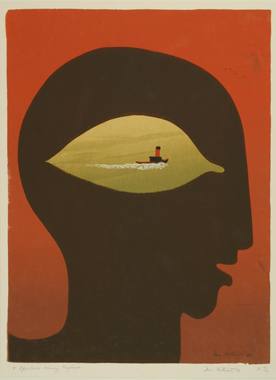

Dorr understood that through carefully placed use of patterned elements—taken from her travels and evidenced in her African Sketchbook—visual music is played with repetition and rhythm. Her artwork is a symphony of Notan. Negative positive figure ground reversals and almost similar yet dissimilar elements organized in an intuitive spacial dance create a joyous, playful repetition and rhythmic accompaniment for the artist’s theme. Dorr’s tonal relationships are like a musical scale, bringing restraint and careful intention to her theme. Consider her serigraph of Island Catnap, or Mendocino Pond Lily. They are humble summaries of ‘place’ at a particular time, and yet they are timeless in their reach for the universal. — Cynthia Charters

•

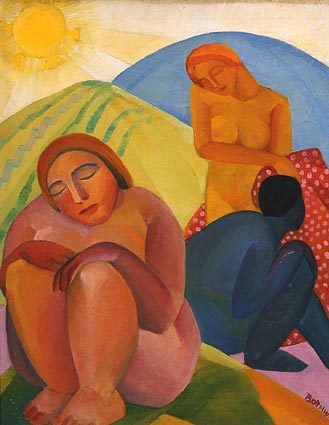

Dorr was the most profound influence on my life and art. In 1953 we were neighbors on Montgomery Street in San Francisco. We had wonderful studios across the light well from each other. It wasn’t until I moved to Mendocino that she became my mentor. We were both involved with the budding Mendocino Art Center. We hung out together and she told me her philosophy of art and life, and I was thrilled. — Charles Stevenson

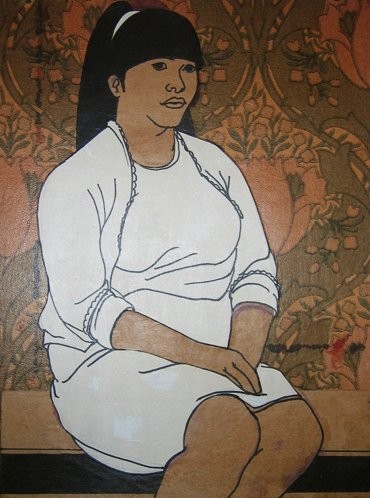

Dorr Bothwell by Charles Stevenson

BACK COVER

“When no preconceived ideas keep us from looking and we take all the time we need to really “feel” what we see—when we are able to do that—that universe opens up and we catch our breath in awe at the incredible complexity of design in the humblest things. It is only when this happens that we regain our sense of wonder.”

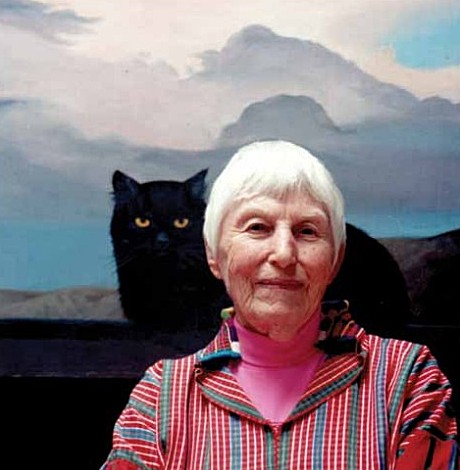

Back cover quotation is from The Innocent Eye, the introduction to Notan. Back cover photograph by Hugo Steccati

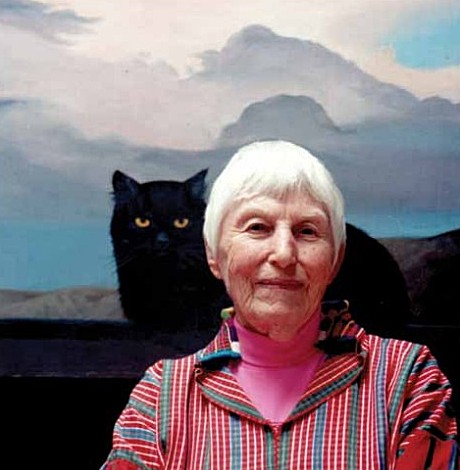

Dorr Bothwell—1997 Photograph by Hugo Steccati

SOURCES

Digital copies of audio and video recordings of Dorr Bothwell are deposited in the Archives of American Art. The audio recordings contain the complete 1987-89 interviews plus other recorded matter. The video recordings are a 1986 class in Color and Design, an undated Notan class, her studio in 1988 (recorded by Richard Karch), and her 90th Birthday Party in 1992, all at the Mendocino Art Center.

All Bothwell graphics used with permission of the Dorr Bothwell Estate. Marlys Mayfield, trustee, 5601 Columbia Ave., Richmond CA 94304.

Bothwell, Dorr and Mayfield, Marlys. Notan: The Dark-Light Principle of Design. Dover Publications, 1991. Bothwell, Dorr. Dorr Bothwell’s African Sketchbook. Monica Hannasch, editor. Arti Grafiche Ambrosini – Roma, 2000.

Graphics on Page 89—Mendocino Robin, 7/62 Graphics on Page 96—Mendocino Robin, 1/63

Brief excerpts from the following interviews and articles were woven into the narrative of the text:

Unpublished letter from Dorr Bothwell to Sally Whitton, 1973

Art Center Treasures by Gerald Huckaby —Arts & Entertainment Magazine

Dorr Bothwell: Art Dynamo of Mendocino by Mervin Gilbert Arts & Entertainment Magazine

Artist Bothwell back for fourth decade of teaching by Kathleen Nevin Mendocino Beacon, Mendocino, California, 4/26/90

Printmaking History—The Forties—by Raymond L. Wilson —The California Printmaker, Issue No. 1, 1/92 Dorr Bothwell:

On the Cutting Edge at Ninety by Antonia Lamb —Arts & Entertainment Magazine, 4/92

Artist Dorr Bothwell by Nancy Barth —North Coast News, Fort Bragg, California, 7/30/92

Numerous California newspapers, published between 1927 and 2000, were reviewed for this project.

BOOK REFERENCES

Acton, David—A Spectrum of Innovation-Color in American Printmaking 1890-1960

Albright, Thomas—Art in the San Francisco Bay Area-19451980

Baro, Gene—30 Years of American Printmaking

Ehrlich, Susan (editor)—Pacific Dreams: Currents of Surrealism and Fantasy in California Art, 1934-1957 Landauer, Susan—San Francisco and the Second Wave

McChesney, Mary Fuller—A Period of Exploration San Francisco 1945-1950

Moure, Nancy Dustin Wall—California Art: 450 Years of Painting & Other Media

Trenton, Patricia (Editor)—Independent Spirits: Women Painters of the American West, 1890-1945

Watrous, James—A Century of American Printmaking-1880-1980

Smithsonian Archives of American Art: Collection Checklist

ART DEALERS

Tobey C. Moss Gallery—www.tobeycmossgallery.com

The Annex Galleries—www.annexgalleries.com

Zacha’s Bay Window Gallery—www.williamzacha.com

Mendocino Art Center Gallery—www.mendocinoartcenter.org

Adamson-Duvannes Galleries—www.justpaintings.net

Spencer Jon Helfen Fine Arts—www.helfenfinearts.com

Douglas Frazer Fine Art—www.frazerfineart.com

Calabi Gallery—calabigallery.com

Paramour Fine Arts—www.paramourfinearts.com

William P. Carl Fine Prints—www.williampcarlfineprints.com

BACK COVER: Photograph by Hugo Steccati. Quotation is from The Innocent Eye, the introduction to Notan: “When no preconceived ideas keep us from looking and we take all the time we need to really “feel” what we see—when we are able to do that—that universe opens up and we catch our breath in awe at the incredible complexity of design in the humblest things. It is only when this happens that we regain our sense of wonder.”

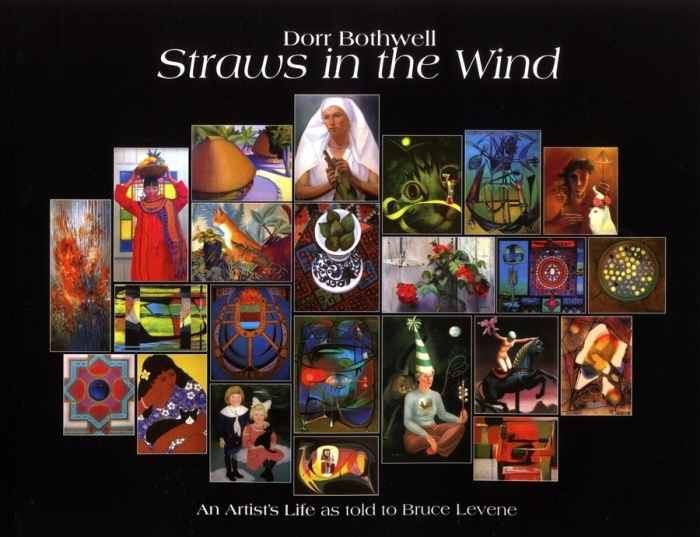

Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind: An Artist’s Life as told to Bruce Levene. Editor, Bruce Levene, art direction for print edition by Marge Stewart. Thanks to Joan Curry, Jane Dymond, Kate Lee, Laurel Moss, Martha Wagner, Jackie Wollenberg, and Jennie Zacha for their past help and encouragement; to the Archives of American Art, Daniel Lienau of The Annex Galleries, Scott Shields of the Crocker Art Museum, Lory Ann Osterhuber of Pomegranate Communications, Stuart Tregoning, and Arlo Reeves for their recent help; to Mara Levene, Samuel Buffone and Michael McDonald of EyesPriedOpen.com for editorial advice; and to Michael Potts for motivating the completion of this work.

Special thanks to Gerald Buck and the Buck Collection, Carol Goodwin Blick, Tobey Moss, and Jason Schoen for their support, to Marge Smith, who transcribed the interviews, and to Marge Stewart of MargeStewart.com for her superlative skill in designing and producing the book.

To my daughters, Mara Levene and Sarah Levene Buffone, and to Gail Lauinger, who stoically observed the meanderings of this creative process.

– Bruce Levene

All works of visual art by Dorr Bothwell are © 2022 The Dorr Bothwell Trust, Mill Valley, California. For permission to reproduce images by Dorr Bothwell, contact

Marlys Mayfield, Trustee, the Dorr Bothwell Trust.

Archive of the Mendocino Heritage Artists

Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind: An Artist’s Life as told to Bruce Levene

NOTE re. Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind: An Artist’s Life as told to Bruce Levene: While oral historian Bruce Levene shaped the story, first by asking questions, then by editing the interviews to form a narrative, the book is not ghost-written, and not a retelling. All the words are Dorr Bothwell’s. Carol Goodwin Blick, Archivist, The Mendocino Heritage Artists

RETAIL: Order a copy of the print edition of Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind: An Artist’s Life as told to Bruce Levene from Mendocino Art Center or Gallery Bookshop (US$24.95, plus tax & shipping). ISBN: 978-0-933391-19-2 / Library of Congress Card number: 00-110686 / softcover, perfect binding, 8.5″ x 11″ / 132 pages / originally published posthumously in 2013 by Pacific Transcriptions, Mendocino, California, republished in 2018 by Christie Olson Day, Mendocino, California.

RESALE: Order copies of the print edition for resale from Christie Olson Day, Gallery Bookshop, PO Box 270, Mendocino, CA 95460. Phone: (707) 937-2215 ext 11. Email: Info@gallerybookshop.com

DIGITAL EDITION: The following is the 2019 authorized digital edition of the 2013 print edition of Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind: An Artist’s Life as told to Bruce Levene. Commercial publication rights belong to Christie Olson Day exclusively. This digital text is available courtesy of Bruce Levene. It is available only for non-commercial use, and only with the attribution: Courtesy of Bruce Levene. If there are questions about appropriate use, please contact the archivist for the Mendocino Heritage Artists. Thank you.

CONTENTS

Introduction

My Family and Childhood

I Begin My Career in Art

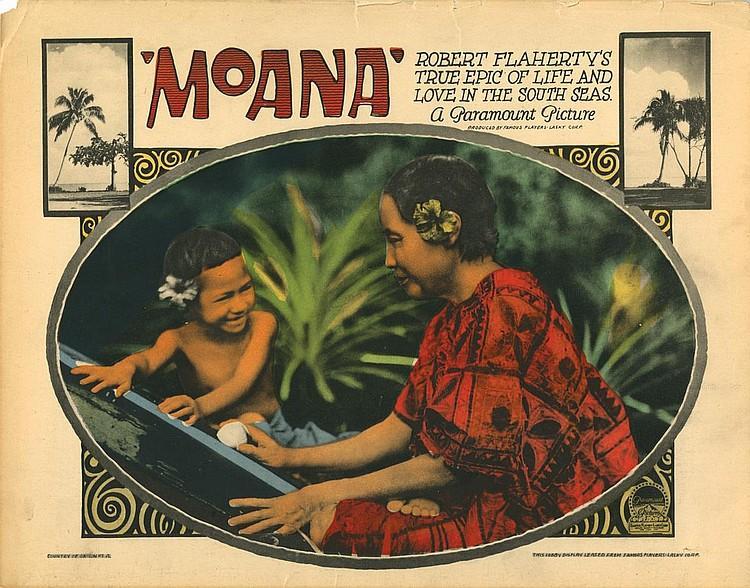

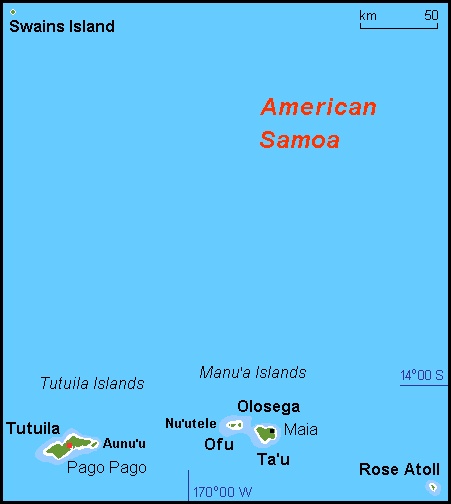

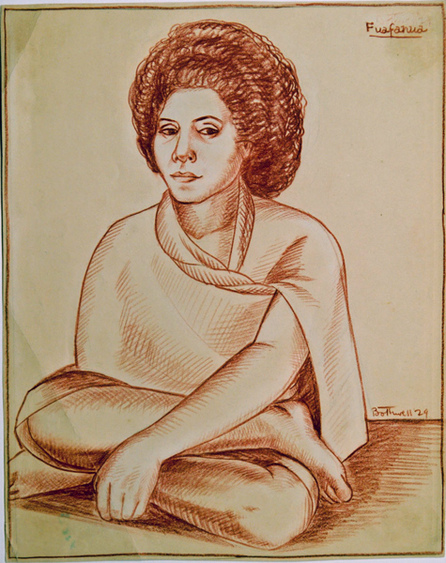

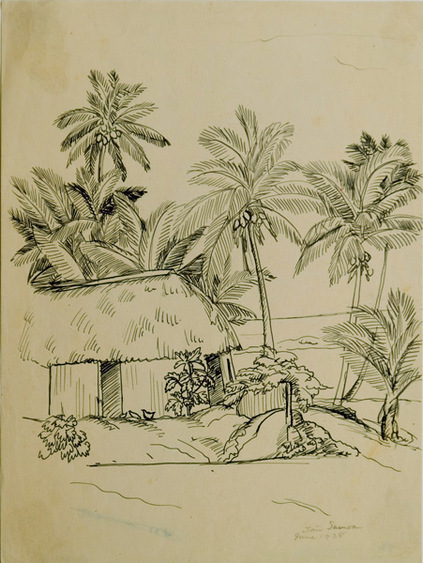

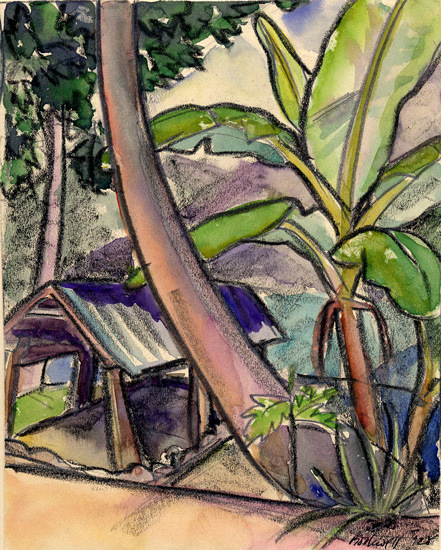

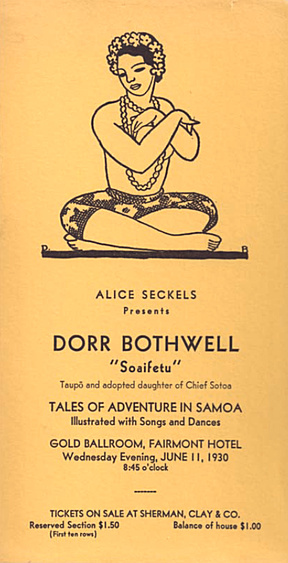

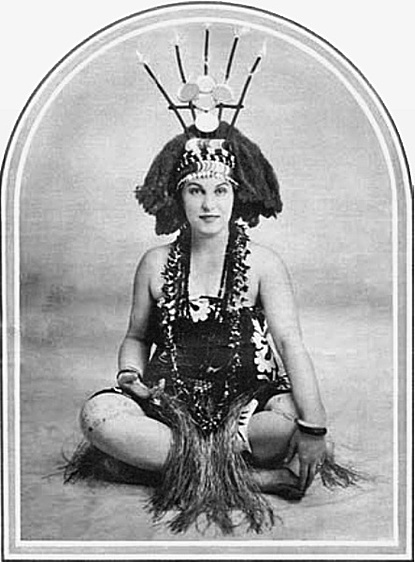

My Samoan Adventure

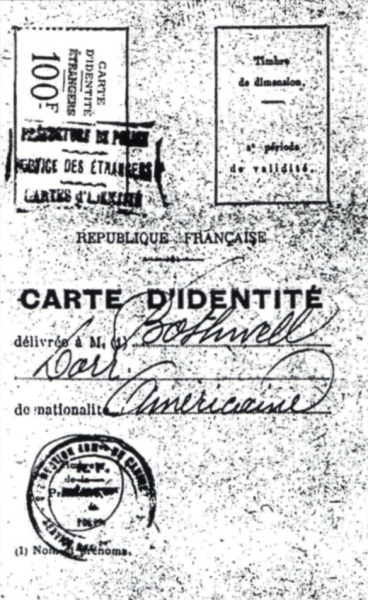

Europe

How I Spent the Depression

The War Years and The California School of Fine Arts

The Paths to Mendocino & Notan

And I Never Stopped Traveling

To Theorize or Not

Tributes

Sources and Dealers

Credits

About Bruce Levene

INTRODUCTION

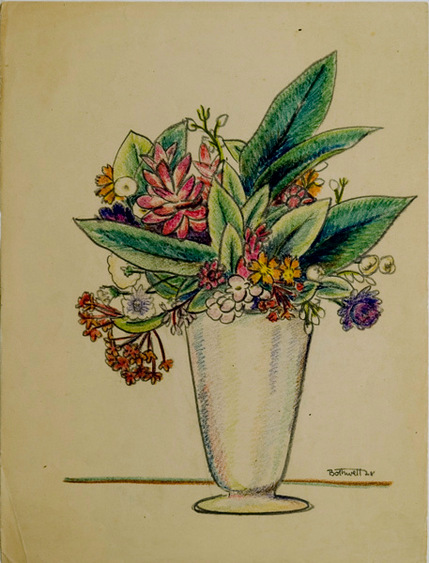

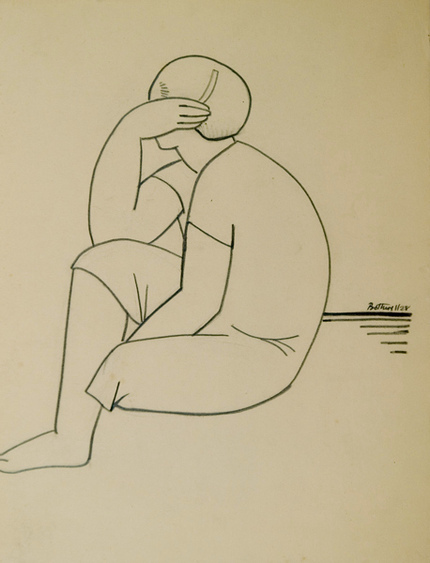

This book was compiled from recorded interviews with an American woman artist whose life spanned almost the entire 20th century. It is an oral history edited from her own words into a narrative autobiography. In addition, more than 200 graphics illustrate the entire range of the artist’s life.

For more than 70 years Dorr Bothwell worked as a fine artist and her life can be summed up by Willem de Kooning’s declaration, “I don’t paint to live. I live to paint.” But her life, though inseparable from her art, was so rich and so inspirational—particularly for modern women—that this captivating story should be shared.

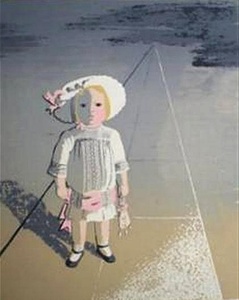

From a transcendent moment in 1906 when she was four years old, until 1997, when her eyes no longer allowed her to paint, Dorr Bothwell never deviated for one moment from her life-long artistic quest. As a woman and a Californian, she faced prejudices and obstacles—and at times hardships—that would have impeded most people. Not Dorr. She continued painting, traveling, teaching and examining new-found paths of her own creation.

Her art explores and describes the patterns of her life—hundreds of paintings, in her own diverse styles, which never stopped evolving, from oil to serigraphy to collage with color laser copiers—and much more in between.

“I really and truly want people to appreciate what’s around them. What I put down, both in color and in line—no matter in what form—I want people to look at it, because it gives them some idea of what is in the world.” Her travels—to the South Seas, to Europe, to Asia—were constant themes and those experiences were usually reflected in her art, sometimes decades later.

For more than 40 years she taught art, usually variations on Color and Design, and more than 50 times her own creative course “Notan: The Dark-Light Principle of Design.” She modestly claimed to have brought the art world along and believed she could teach anyone to draw. Her students never forgot her enthusiasm while showing them how to see the beauty and design underlying light and color.

She was unconcerned about her place in art history—as long as the public and a myriad of collectors purchased and enjoyed her works, that was enough.

Dorr Bothwell died in 2000 at age 98. A memorial, attended by many friends, was held on the Mendocino Headlands. As she requested, her ashes were sown into the Pacific Ocean, along the California Coast which had nurtured her for almost a century.

An observer might have recalled the old Gaelic blessing of the artist’s Scottish forebears: May the road rise up to meet you. May the wind be always at your back. May the sun shine warm upon your face. May the rains fall soft upon your fields and may God hold you in the hollow of His hand.

Dorr Bothwell was the invincible spirit of American Modernism, the epitome of artistic creativity during the 20th Century.

— Bruce Levene, Mendocino (2013)

MY FAMILY AND CHILDHOOD

In 1790 a ship sailed from Scotland filled with ghillies (workmen) of the Clan McNab, together with some non-clansmen. The men were heading for a wilderness in northern Ontario filled with wild animals and Indians. They represented all different trades except baker and blacksmith. To resolve this crucial problem they drew lots and the young man who drew the shortest straw became the blacksmith. He was William Bothwell.

He had been listed as a teacher, but as there were no women or children, he accepted the job of blacksmith and never did teach. He spent the rest of his life pounding an anvil and became a famous wheelwright in northern Ontario.

William Bothwell married and fathered 13 children. The youngest child was James Bothwell. James married and had four children—two girls and two boys. The youngest boy was my father, John Stuart.

They lived far up north. When John Stuart Bothwell was growing up the nearest neighbor, 40 miles away, was the Hudson Bay Company trading post. In time farmers came in and finally a school was built within walking distance, about five miles away.

My father, like William Bothwell before him, had a great yen to see the world. When he came of age and finished his education, he left Canada, because there was little opportunity at home, and went to the United States, where he heard there was work. He got a job in New York trying to collect bills that nobody else could collect but that didn’t last very long.

Eventually, when he was in his early ‘30s, my father got another job that took him to Chicago. After arriving there he needed a place to stay. In those days, without radio or any kind of easy communication, there were local ethnic newspapers, generally two or four sheets. Father bought a copy of the one for Canadian and British people, a weekly newspaper called Canadian American. The newspaper told about people who had arrived from Canada or from England and similar stories, but it also had advertisements for places to stay.

My father was older than most of my friends’ fathers because he married late. He was the first Bothwell ever to marry someone who wasn’t 100 percent Scottish. My mother, who was English and Welsh, would have been considered a foreigner by the Bothwells. Her maiden name was Hodgson, my middle name.

My maternal grandmother, Emma Elizabeth Hollingsworth, was the youngest of a fairly large well-to-do family and took after the Welsh side of the family. She was tiny, about four feet eleven, with black hair and dark brown eyes. She lived in London.

My maternal grandfather, James Terhume Hodgson, came from a wealthy Lancastershire business family and had started out as a successful young businessman himself. His parents had a huge manufacturing plant in Rotherham, on the River Rother, and he was all set to marry the daughter of a similar manufacturer. The marriage was planned but the banns had not been posted.

How my grandparents met I never heard, and I don’t think even my mother knew, but what happened was that Grandma and Grandpa fell in love and eloped.

The reaction by their families was immediate. James Terhume was disinherited, with a “never darken our doors again” attitude. I don’t believe he ever went home again. He was probably disinherited by mail.

And Grandma was disinherited also, because her parents felt she had married beneath her station. This was very serious in those middle Victorian times, 1859 or 1860—a sense of propriety! The idea of Grandma running away with somebody ‘in trade’—as business was called then—was enough to disinherit her. My grandmother’s family sent out black-bordered letters saying that their daughter had disgraced the family, or words to that effect and that she should no longer be considered part of it. And they almost—I don’t think they ever said it—let it be known that she was no longer alive.

I’m not sure if they even let her in the house again, even to get her clothes. I think somebody packed everything up and put the trunk on the front porch. So overnight both of them were, so to speak, without any family at all.

In Grandma’s case, she never mentioned her family. I don’t know if she had siblings, except for one sister, whom she referred to as “your great-aunt Alice.” When my grandmother was pregnant with her first child and they were still in England, her eldest sister Alice sneaked away and visited her. It may seem pitiful now, but at the time that was a great concession on the part of my great-aunt. This was the first news that Grandma had heard of her family but she never saw any other family members again. As far as I know, no one in my grandfather’s family ever spoke to him again nor did he receive one cent from them, either.

So how did they live? It was as if they were tourists in England. There was no place to go; nobody welcomed them; they were without any property, with little more than the clothes on their backs and what little money my grandfather had. But Grandpa was very smart. He became an entrepreneur and began to buy up the patents for what he felt would be successful inventions. And they were. He traveled continually, buying up things and going to outlandish places. He had a shrewd eye.

My grandparents spent the rest of their lives traveling. After a year or so in England they went to Sweden.

Grandma, trying to keep track of her children, had the habit of giving the child a name characteristic of the place where he or she was conceived. The first child, Uncle Harold, had been conceived in England, naturally. The second child was Auntie Hilda, conceived in Sweden, then Aunt Maria Teresa in Austria. Then there seems to be a gap.

Grandma kept having children, but they continued to die. In those early days their travels meant difficulties, like proper food, and I guess that changing from one hotel to another was lethal. All the children died except four.

Grandpa bought up wonderful inventions. He bought the patent to a meat slicing machine, which he sold in England and Scandanavia. He bought some kind of spinning thing, took it to India and made a killing! He was a sharp business man. He was in Greece and India, then South America.

Grandma faithfully had a baby almost every year. After 15 years, in 1875, my mother, the youngest of the 11 children, was born. You can guess where she was conceived, because she was named Florence Isabel—Grandma must have been unsure whether she was conceived in Italy or in Spain.

Grandpa eventually cornered the market on whalebone. Hoop skirts were in fashion and he was doing very well. But he over-reached himself when he decided to sell patents in America. Moving to the United States, the family went from—I don’t suppose it was in the millions, but close to it—to absolute rags. Just about that time hoop skirts went out of fashion. On top of that he had just purchased one of the first lace-making machines in Switzerland and brought it to the United States; but no one was interested in the machine and he had trouble selling it. Only hand-made lace was fashionable and machine made lace was considered déclassé.

The family, consisting now of my mother and, I believe, one or two aunts, got stranded in Chicago. Grandpa and Grandma bought this big mansion in a little suburb called River Forest but they were broke. My grandmother didn’t waste time. Although she had grown up in luxury, she took charge, opened the house up to take in boarders, and listed her boarding house in the Canadian American.

My father read the advertisement, stating that an English family offered room and board in River Forest and out he goes. My mother answered the front door and they fell instantly in love—something that seemed to run in my mother’s family.

My mother was a very forward-looking person. She went through high school during the 1890s and was so smart that she finished when she was 17. The year before she graduated the 1893 Columbian Exhibition took place in Chicago, where she saw all the new inventions. They so excited her that she decided to become a business woman. She turned down the university idea, because they didn’t teach business, and went to a business school. She loved the idea of planning things and even memorized Robert’s Rules of Order. She had a brain!

Mother was a perfect Gibson Girl, with starched shirtwaist, her hair done up on top of her head in a pompadour. She worked in an office, for peanuts, because women were really put down then. But because she could type and take dictation she got the job.

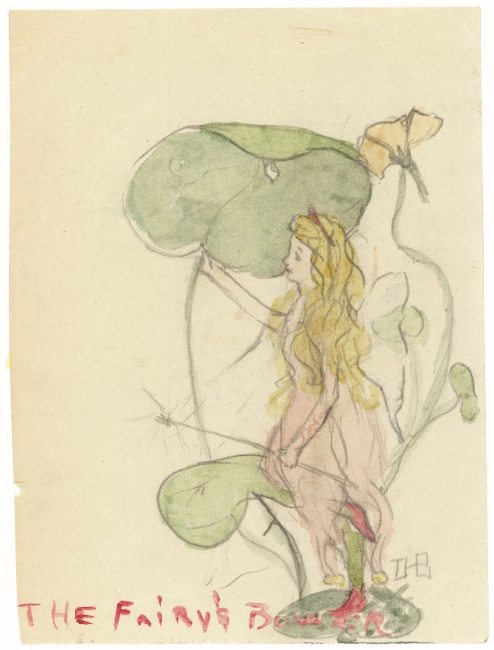

Grandma made sure, however, that my mother had all the niceties of a Victorian lady. Well brought up young ladies played the piano and did watercolors. So on Saturdays my mother took private lessons in watercolor painting. She was very lucky, because she had a teacher with real talent.

My mother was very happy with her life. She had become an American citizen when she turned 18, having been in the United States long enough to get her citizenship papers (she lost her American citizenship when she married my father, a startling example of the status of women at the turn of the century). She was the only American in this English family and very proud of it.

Father lived in the boarding house for about six years. Eventually he and Mother became engaged and it looked like they would follow the usual pattern—they’d get married and probably go to Toronto, because generally the husband took the bride home with him.

About this time the machines that made lace began to sell, so my grandparents had some money. Grandpa had also applied for an American patent for the Swiss meat-slicing machine and he managed to recoup part of his fortune before the designs were copied.

But they were still taking in boarders. Then comes the wonderful story of how my parents got to California, which is hard to believe and sounds like something out of a novel, but is true, because fate, waiting in the wings, had something in store for them—my Uncle Harold!

Uncle Harold, my grandparent’s first child, survived because he was not dragged around traveling. In fact, the first three children were probably healthy because they were put in boarding schools. It must have been lonely growing up with your parents away all the time and perhaps that’s what put a kink in Uncle Harold’s mind. He had a very elegant education. He didn’t go to Eton; he went to a lesser boys’ school—either because they didn’t have the money for Eton or because he started out there and couldn’t finish up. He was a Victorian gentleman, but in spite of education and upbringing, he became a professional gambler.

He went anywhere there were good casinos or good horse racing. He particularly liked to watch little Mongolian ponies race and had traveled to China, perhaps even to Japan, and any place in between where there was racing. He just traveled continually all over the world. So he was not really an active member of the family.

My brother and I knew there was something bad about Uncle Harold because we’d never seen him. We were never allowed to say, “I bet you.” We couldn’t play any kind of betting game, even with matches, because this horrible taint might come out in later years.

Just after my parents became engaged, Grandma received a cable from Harold, who was in Cannes, France. He’d been gambling in the casino with a California rancher. Harold had won the rancher’s yacht and all his money. The man wouldn’t give up and he slapped down on the table a deed to his ranch in Rumsey, California. Harold won the ranch, too.

But Harold was heady. He kept gambling and lost everything, except the yacht and the deed to the ranch. He sailed as far as Marseilles on the yacht, but the auxiliary engines ran out of petrol plus he couldn’t pay the crews’ salaries. So he gambled with a ship chandler (a maritime supplier) and lost the yacht and his money. Harold was flat broke in Marseilles but he had the deed to the land. He cabled my grandmother for money, telling her that he had security for a loan.

My grandfather was so disappointed with his only son that he wanted nothing to do with him. So it was my father who counseled my grandmother in this crisis. My parents weren’t married yet, but naturally Father had a great interest. He told my grandmother, “Your fortune is just dwindling away. You should not just give him sums of money all the time without some security. Cable him and ask what security he has—he’s told you this before.” So she sent Harold a cable.

Back came a four word cable: “Have deed California ranch.” Apparently Harold had enough money for cables, which were expensive. Grandma cabled him the money.

Eventually the deed to the Rumsey ranch in California arrived. My parents had decided to be married in June, 1900. Mother was 25 years old. I think Father was 36. The wedding date was rapidly approaching and Grandma saw an opportunity. She said, “Take this deed, when you get married, and go out to California, and see what this ranch consists of. If it’s a profitable thing, keep it. If it isn’t, try to sell it.” Mother got rid of her fur coats and her heavy clothes and came out in a little white lawn wedding dress.

They were married, and with the deed in their hands got on the train—it’s a long train trip—and started out for California.

The only thing of note about the train trip going West was that their seat mate was the famous metaphysical sage and spiritual teacher Vivekananda. My father had an inquiring mind and was hungry for this kind of wisdom. He loved history. It meant a great deal to him and I think he was able to understand many things beyond his time. I realize, looking back, that he was way ahead of his time in how he looked at what was happening to the world. I really think that his meeting with Swami Vivekananda could have contributed to that.

Finally the train trip ended and my parents took the ferry across San Francisco Bay to San Francisco. Mother, being a city girl, was entranced with The City. They spent a few days recovering from the train trip. Mother didn’t want to leave but my father said, “We have to go and see this ranch.” This meant another train and a long horse and buggy ride out to the ranch in Rumsey, California.

I once checked all of this out. I found the various deeds, how Harold first had the ranch, how it was then deeded to my grandmother. It was all true.

It was a wonderful ranch with peach orchards and numerous buildings. There were horses, and chickens, which my father particularly liked. Anything that multiplies, I think, especially by themselves, interests people who like mathematics, which was my father’s field; so he loved it.

They spent an idyllic year there. Imagine a honeymoon on a beautiful ranch, with fruit trees and flowers. Beginning the second year Mother was pregnant, with me. But she was not—I guess from the experience her own mother had of having so many babies die here and there—about to be out in the middle of an orchard when her baby was born. Mother was a city girl and wouldn’t stay on the ranch, so my parents sold it. Mother got her way and they went back to San Francisco.

Dad never saw his parents again, because Mother wouldn’t travel and he wouldn’t leave her.

In those days travel was quite difficult. Even when I took the train to New York 50 years later it took 4 days and 3 nights on the train. People today don’t realize how hard it was. And going up to Canada you had to take the train from Chicago and go over to Windsor. The trip would not have been easy, so my father never went to visit his family. His father had been killed when he was a young man. I remember, very vaguely, when I was quite small, that Father would get letters from his mother—then they stopped coming.

We also moved a good deal. Dad didn’t want to buy property here. He was not an American citizen and had no intention of becoming one. He inherited property in Scotland and could have gone back there and fit right in. But Mother wouldn’t budge. So he let that property go to the next inheritor. He chose not to go back to Canada either, although he would have had some advantages there.

Most likely he didn’t want to return to Canada because we had no relatives left there, to speak of. Of my great-greatgrandfathers’ 13 children, 2 girls married but had no children. Only four of the men married and they all had sons, who were our first cousins once removed—but were also the proper age to join the Canadian Army during World War I in 1914.

The Bothwells in Ontario were all settlers who had been in Canada for generations; naturally they kept close together and were like one big family. But all the boys—cousins and everyone else—joined the Princess Pat regiment, which suffered frightful casualties in the War and wiped out a tremendous number of Canadian families—it just cleared the settlers out.

So we rented houses. We were always renters. Wherever we rented, Dad gardened and the place just looked wonderful and was always painted and kept up. He was a great organizer.

I often think what might have happened, because I could have been born either in Canada or in Scotland. I wouldn’t have been an American. But both my brother and I were born in San Francisco and became Californians. Mother loved the place and never wanted to leave.

I was born May 3, 1902, on Post Street, between Scott and Divisidero, in one of those buildings with an immense, steep staircase. My parents had a flat on the second floor and in those days you were born at home. When I was three, we moved across the Bay to Alameda—1911 Pacific Avenue.

In April, 1906, the San Francisco earthquake occurred. I was not quite four and my brother was three. It happened early in the morning. I remember standing in my crib, yelling “Wheee,” because it had castors and was going back and forth, rolling from one side of the room to the other.

My father had the presence of mind to turn the gas off. We had gaslights in that part of Alameda. Not everybody had electricity. The dawn was coming up so it wasn’t too dark. My father had Mother stand with her back against the door-frame. She held my brother Stuart in her arms. Dad tried to put his hands on each side of the door frame. The house first started shaking one way, then it got a big swing going, then it went “pom, pom, pom” in the opposite direction. My father fell down on the floor. Since he was a teetotaler, I had never seen him down on the floor and that was a startling image that has stayed with me.

Then there were two tremendous crashes! First the bricks fell on our roof from the chimney. Then this huge Welsh dresser, filled with the family porcelain service, walked out from the wall and fell flat, destroying absolutely everything except one tiny covered ramekin. This was pretty white porcelain with a deep turquoise blue band, and a gold band around that with Grandma’s entwined monogram.

There were all kinds of noises. Part of our chimney jumped across the little gap between the houses and fell on our next door neighbor’s house. And the chimney of our neighbor on the other side fell onto our house.

My memory of the following day is one of great confusion, with strange people in our house, strange children, and everything mixed up. My father was deputized to go into his office building in the closed-off section of the business district across the Bay in San Francisco. It was necessary for him to get something out of his company office to take to the bank for storage, in case they had to dynamite the building to halt the fire. Mother begged him to take me with him, because she had her hands full with my brother plus a couple of children whose mothers had been injured. She simply couldn’t cope and I would be a nuisance to her otherwise.

So my father took me with him. There was no transportation and we walked up from the Ferry Building. I remember standing for what seemed like hours, down in the ground floor of the building, while my father climbed the stairs. No elevators worked. Then we went to the Hibernia Bank, which was crowded with people depositing their money, because that building was the safest place. My father went in to the bank, but he didn’t want me to get pushed around by that mass of people, so he left me standing there all by myself.

Two blocks down from the Hibernia Bank was the Treasury Building, which had been shaken flat down and burned. A ring of uniformed men sitting on horses, who must have been soldiers, surrounded this place where nothing but a plume of smoke came up. Later my father explained that they were guarding the safe, which was too hot to open, to prevent looting.

As time went on I got thirstier and thirstier. I was crying by then—you know how children are. Dad tried to find a place for me to get a drink of water and had to carry me once in awhile. We finally wound up in Chinatown, at Portsmouth Square, where a Salvation Army lassie, complete with bonnet, had built a bonfire in the gutter of the Sacramento Street side. She had an enormous gray granite coffeepot, as big as I was, on the fire. My father asked her if she had any water but she said that all the water was contaminated. But if he’d wait awhile, she would give him a cup as soon as the water boiled but before it got too strong. That was my first drink of coffee, which tasted terrible, but at least it quenched my thirst.

The thing I remember most was a steady moaning sound. Years later I asked my father if he remembered it and he said, “Yes, that was the wailing of all the Chinese people.” Because the Chinese weren’t allowed to move out of Chinatown, they had tunneled down three or four floors below ground. The earthquake caused the buildings above to collapse and many people were buried alive. There had also been many other injuries. Women and children were sitting crying on blankets in little Portsmouth Square or were huddled in front of the Hall of Justice on Kearney Street.

Something else I remember was that people, mostly men, looked straight ahead, in a kind of a blank stare, and that my father had to continually jerk me from side to side, out of their way. I was used to people giving way and not stepping on a child, but these people didn’t see anything. They were in what we would now call complete shock, just wandering along the street.

That same year, when I was four, I had an extraordinary experience. I remember my part of it clearly and my folks remembered the other part. I had been very naughty. And I knew it, knew that I deserved the spanking I got, and also that I deserved to go to bed without my supper. Heaven only knows what I had done. The memory I have is of wiping the tears off my face and being put to bed. I wasn’t too hungry—I didn’t care about that. I was really ashamed of myself.

My grandmother was staying with us then. Grandma was an early Quaker and she thee’d and thou’d us and taught us about praying. My father was brought up in the Scottish Calvinist religion, which he rebelled against completely, and renounced as soon as he could. So we were sent to Congregational Sunday School—they felt that was safe.

This is all by way of saying that we were brought up to talk to God. And God is not a man in a white shirt way up in the sky, but a point of light within you. It’s called a seed of light and you are joined to this God—you cannot escape. He sees everything you do. But, also, he is love and you can talk to him.

So I was praying to God, talking to him, telling him I really was sorry and I would like to have him please make me a good girl. I was lying on my back. Suddenly, from near the ceiling but at the foot of my bed, thousands of tiny, very small, colorful, bright lights began floating overhead, moving fairly rapidly. The lights were about the size of those glass-headed map pins that the teacher used to put in the map on the wall in school to mark a special place. Now I would say these lights were like seeing neon from a plane about 5,000 feet up in the air, but of course we’d never seen anything like that.

They were all colors: pink and blue and yellow and cerise— really beautiful. There were just clouds of them. I watched as they came up from the foot of the bed and floated over my head. I remember trying to watch them go over, because I turned my eyes back as far as they’d go to see where they went and the lights would go way back of my head.

Then a presence entered the room and it was neither light or dark—it was just a presence. It was at the foot of the bed; then it divided itself. Then it was on each side of the bed. Then one part of it went back of the bed, took me by the hair, and pulled me backwards. And that’s all I remember.

The family story is that when I came in the next morning I apologized to my father and my mother and to my grandma for being so naughty. Then I sat on my father’s lap and said, “Daddy, what’s a nartist?”

My father was a purist when it came to language, a stickler on pronunciation. So he said, “What you’re asking is, what is an artist?” I knew my cue was to repeat it correctly, so I said, “What is an artist?” Father said, “Well, an artist is someone who sings, or writes poetry or paints a picture”—and he pointed to the calendar, probably some hideous chromo—“like that landscape there. Or like your mother does watercolors.”

And I said, “Oh, well, that’s what I’m going to be. I’m going to paint pictures of everything.” And I climbed down from his lap and went over and sat in my chair, ready for breakfast. I said it very firmly, so they told me. That was it. And I never varied from it.

While he was still in Chicago, my father had been offered a post in Toronto, teaching mathematics, but Mother wouldn’t go. So when they got to San Francisco, he didn’t have a job, and only a little money from the sale of the ranch.

But he had a gift. He was a lightning calculator. It was something he couldn’t explain, because he didn’t know how he did it. He would look at the figures and kind of squint his eyes, then tell you what the total was. He had great patience, but could not understand why my brother and I held our fingers up when we tried to add.

Dad got a job with the Emporium, naturally in the accounting department. Then they found out he had this gift. Well, they paid people two ways, either by the hour or by the day, either in silver or gold. Paper money wasn’t used much then in the West.

The white collar people were paid in gold. Most of them had a little chamois bag with their names stenciled on it. They received this in a white envelope with their name on it, because naturally they were gentlemen, you see, white collar. Finally my father got to the place where he became a gentleman once again and had his little chamois bag with the gold coins. I just loved them. They had $50 and $20 coins. I still have a $2.50 gold coin with an Indian head on it.

Because of this gift, his lightning calculator mind, my father had the ability to handle big figures. So he finally went into the lumber business, with the McCormick Lumber Company, headquartered in San Francisco. He always was in the accounting department, or treasurer, anything that had to do with figures and money. Lumber is figured in the millions of board feet and they did not have adding machines then.

When Haley’s Comet came around this last time, I suddenly remembered its coming in 1910. The newspapers would give the mathematical degrees of tangent because they just didn’t have enough people to work on the calculations. While they were working, the comet was moving and the scientists were trying to do all their figures. They’d give out certain problems for anybody interested in math who could help solve them.

Now you’d do it on the computer, or before the computer, on the comptometer. They printed the whole thing in the newspaper and my father adored it! He’d get the newspaper and his pad of yellow paper and he did beautiful figures and he’d say, “Oh, wonderful! Just put this down . . .” He was gone. He’d do this whole thing and send them in.

Both my brother and I went to a private school first, in Alameda. The public schools were damaged during the earthquake and this small low building had been a private home. A lot of Canadians and the English had moved to Alameda. I think that’s why we did, too. My school was what the English called a Ladies’ School but they took both little boys and little girls. After the public school was repaired, my brother and I went there.

Down the street, on upper Pacific Avenue, there was a large house with a fence and I’m amazed that I can still see the design—we left Alameda when I was nine years old. It was the most beautiful cast iron fence, designed like ears of corn, with flat leaves going around it—a bar relief, actually. I just loved that fence.

At the end of our block was a small fire station. The fire engine used heated steam, which was different from the bigger hook and ladder engines. They had two dapple-gray horses, Clydesdales, with all that hair and huge feet. And those horses knew exactly what they should do. I don’t know how the firemen knew where the fire was, because telephones were just coming in and in 1906 few people had telephones; but I’m sure the Fire Department did. They would ring the bell, and slide down the poles. My brother and I would run as fast as our little fat legs could carry us and stand behind a wall to watch the horses and the engine.

In 1911 we moved to southern California. My father’s company opened a new branch in San Diego because of the need for lumber in the building boom in the Imperial Valley. The area had been an uninhabited desert, but the discovery of artesian wells meant irrigation ditches and development. Dad went down to head the San Diego branch.

Everything we owned was packed up and shipped down on a schooner owned by the lumber company. We took the train to Los Angeles and explored that city, which seemed to be nothing but one orange grove after another, with houses scattered in between. My father found a house for us. The furniture arrived in a few days.

My father wanted us brought up in the country and, in 1911, San Diego really was the country. It was small but very nice. The town had delusions of grandeur, with sidewalks and paved streets and completely vacant lots. Mexicans would come up with goat herds and pasture the goats in the canyons below Balboa Park.

We lived on Louisiana Street at University Avenue. There was nothing there. There were three houses on our part of the street. Now, of course, it is so built up you can’t even find it! There was a library at the end of the block. By walking about three blocks, you could hit El Cajon Boulevard.

San Diego was delightful. We weren’t used to living in, what seemed to us, a semi-tropical climate. Most of the surprises were pleasant, but not all. Our first encounter with a tarantula left even my father somewhat shaken, although he’d been accustomed to encountering wild creatures in northern Ontario. A little research reassured him that they were benign as far as human beings went.

Our new house was the type known as California bungalow. It had the usual blocky square, slightly tapered, wooden columns holding up the front porch roof, and something that seemed symptomatic of southern California living, a large chimney studded with cobblestones. Another attraction, especially from my father’s point of view, was that you could grow geraniums all year around. He immediately planted loads of red geraniums. Mother liked the idea that she could easily grow lettuce and other vegetables year round. She changed our diet radically.

University Avenue had a streetcar that we could take to Park Boulevard, then transfer. If it was rainy weather the streetcar took us right by the school just a few blocks away. My father estimated that we certainly could walk it. It seemed like a long walk to us as small children, but we soon managed to figure out short cuts. We generally found creatures to watch for—a toad that lived in what was possibly a box for a gas or electricity outlet. Loads of wild flowers. We would arrive at school a bit disheveled, but certainly relaxed.

My father wanted us to get a decent education. He considered American schools very poor. He had learned his Latin when he was 12, his Greek when he was 14. He couldn’t understand a grammar school without Latin.

I was nine years old when we got to San Diego and that put me in the upper third grade. My first teachers were Miss Greer, who was cute, with brown hair, parted in the middle, and big brown eyes, and Miss Hammock, who had kinky reddish-blonde hair, blue eyes, and was kind of plumpish, medium size.

Our school was unusual, because it was the experimental grammar school on the same campus as the State Normal Teachers College. Professors who taught and monitored the teachers also came into our classrooms. However, it was much more than that. The principal of the school, Gertrude Laws, was a modern educator who became quite well known in educational psychology. The faculty consisted of good professors in their own right.

They would demonstrate to student teachers how to present certain subjects. I vividly remember Professor Bliss, an English historian, telling us—we were just beginning to learn about Shakespeare, probably in the fourth grade—how English sounded in Shakespeare’s time, explaining how words changed, and how different words were pronounced.

There was Mr. Skilling who, when the First World War was imminent, showed us how to make little gardens. We had little plots of land and learned how to plant. He also told us about constructing houses.

We had a wonderful teacher, Miss Judson, who went to Germany during her summer vacation and brought back those large red-labeled single side Victor Records of Wagner’s Nibelungen Ring. Since it was a State school, they had a great big Victrola with the top coming down, curved, red mahogany, and little doors with brass knobs—you opened those up for the sound, then you wound it up. She didn’t play the whole piece of music, but she played enough and explained it to us. She was head of the music department for the teachers, but she also experimented to see if we could retain musical ideas. She would explain a motif, then sit down at the piano and play it. We’d listen to her play, then hear the motif played by the orchestra on a record. She demonstrated how the melody appeared and guided us through the music. When this motif was played we knew that certain characters were about to come on and sing. Oh, I just thought it was wonderful, because I had been brought up with music.

Miss Judson also had what really thrilled me—one of the earliest naturalist recordings of birds, the song of the nightingale. I had read fairytales and had wondered what a nightingale sounded like. It was a very moving experience as far as I was concerned.

We also had a number of Spanish speaking children, who had escaped with their families from the Mexican Revolution. Senora Rosalie gave a short class every day in which some of us learned Spanish and the Spanish students learned in English.

The outstanding thing was to be taken into the teachers’ assembly room to see something called a Bilocticon. You could open a book with an illustration, put it in this machine, and it would appear on the screen. It was used before overhead projectors. I’ll never forget this. They had a book on Italian frescoes with colored illustrations. In those days they were colored lithographs, but they were beautifully done. A teacher would project one on the wall and tell us all about it. It made a tremendous impression on me because I was so hungry for anything that had to do with art, and even though I didn’t understand what I was looking at, I was thrilled to see these wonderful images.

We also gave school plays, read the Aeneid and acted it out. We designed our own helmets and everything else when we were in the fourth grade and low fifth. It was wonderful! I had a choice, I could take cooking and sewing or Spanish and typewriting. My family split on that. The first semester I took cooking and sewing. They were glad to get rid of me when I took Spanish and typewriting the second semester. I’m still typing. I do touch-typing and you never forget it.

My grandmother would come to visit us every few years. Then, after she returned to her home in London, she would go over to Paris and buy us clothes. She had our measurements and allowed for our growth. Soon a trunk would come with all these wonderful hand-made clothes.

But not a single child in San Diego, California, was wearing things like we had. I didn’t care, but my brother would get so upset because he didn’t look like everybody else and would cry himself into a fever.

I remember he wanted a beanie, a hat that you turned up and cut the brim in little spikes around the edge. Then you put campaign buttons all around. I think he was about 10. All the little boys in his school were wearing them. My father just could not understand this—he didn’t have much sympathy. But finally they had to give in because Stuart cried himself sick. I mean that—he was in bed!

I didn’t care what the other kids said. I’d just fight them if they made fun of me. I’d kick them and throw them down and do all sorts of nasty things. I was probably the only child in San Diego, I’ll have you know, wearing a linen lawn pinafore with ruffles over the shoulder. It was all hand-made, hand-tucked with hand-made lace! I wore it over pure linen dresses that had box pleats front and back with a patent leather belt. Kind of like a Mary Jane type dress. When you sat down, it all crushed and I always had to keep my dress clean. Here was this little white pinafore on top of that. I had long hair and they’d pull it.

Grandma was very elegant and had an upper class accent. In spite of being disinherited, she had her education. She used to say, “I wish I had retained my accent.” But my brother and I were teased when we went to public school in San Diego because we both had English accents, with a little bit of influence from my father’s accent—not broad Scots, but with a slight burr on the tongue. The kids called me ‘limey.’ So, in desperation, we got rid of our accents.

My friend, Margaret Bennet, came from Indiana and my brother and I copied her accent—that’s why I’ve got a hard Indiana ‘r’. Oh, finishing schools would just have hired me out of hand if I’d had my grandmother’s accent.

Grandma’s manners were very Victorian. She kept her elbows in at her sides. We practiced sitting up straight. She really trained us.

It was very difficult in school, especially the early grades. Nobody knew what they were going to do. Margaret would bolster me up, although she didn’t know what she was going to do, either. We made paper dolls together and that sort of thing.

My mother took watercolor lessons and our house was filled with her framed watercolors. Not little twiddley things. Over the mantelpiece was this elegant bouquet of red roses, a nicely framed large watercolor at least 24 inches by 28 inches. She had other watercolors that her teacher had her copy, but some were Mother’s own interpretation, so I knew that such things existed.

But I still insisted on what I wanted to do. Mother let me play with her watercolors. What I really needed was guidance, even though Mother’s paintings were very important to me. But since painting was considered something few women were successful at, I was steered into music (a woman could be a successful accompanist to a virtuoso violinist and share in reflected glory) and the ballet (not quite as respectable but still not the theater!).

For some reason my father felt that being an artist was sort of an idle profession, so I was given every other chance not to be one. I studied music with a gentleman known as Professor Wrinkle, a German who had worked with a well-known Bach annotator. He gave me a good grounding in technique, although not so much in the music. And I was enrolled in a ballet class.

I must tell you a story about my dancing career. My ballet teacher in San Diego was a Mrs. Ratliff. During World War I, Anna Pavlova, the world-renowned Russian ballerina, came to California to recuperate from a big tour in South America and in Mexico City. Because of the war she couldn’t return to Europe, so she stayed for three months in Los Angeles and gave a few classes. Ballet teachers from all over, including my teacher, went to Los Angeles to study with her.

Then Pavlova decided she really needed a rest, so she went to San Diego, which was much quieter. Mrs. Ratliff persuaded Pavlova to come to our class one morning and just stand in the doorway of the classroom.

Mrs. Ratliff had a lot of little toddlers, plus medium sized kids who were good in acrobatics, and a handful of what we considered the adult class. I think we were 13 and 14. Most of us were still growing. I, however, was the same size I am now, five feet, two and a half, which made me one of the tall ones.

The little ones who were on the half toe were supposed to run forward, curtsy, then run off to the dressing room. The girls who were doing more acrobatic dancing were supposed to do a few cartwheels, curtsy, then run off to the dressing room. Finally, we so-called adults were to travel on our toes—on our points, as they say—make an elaborate curtsy, then run off.

I decided to let everybody else go first. Well, the three or four ahead of me did a beautiful job. They were lovely. And, of course, with my incredible ego, I decided that I would do this so perfectly that Anna Pavlova would recognize in me the future ballerina of the world.

I started off and I must say I did a very good job until all of a sudden I was traveling on my toes so fast that my left foot kicked my right foot out from under me and I fell flat, knocking myself completely windless. We had all taken falls and were trained how to get up gracefully. But I had never been trained to take a fall where I lay flat on the floor, without any breath. So I did the only thing I could think of—I rolled over on to my knees. I was so disappointed in myself that I didn’t even bother to do a curtsy—I just ran toward the dressing room on all fours, with my tutu, my skirt, over my head, my pink pants showing.

We didn’t wear long fancy hose or anything. We had bare legs. So here was the rear end sticking out in the pink pants, bare legs, running off to the dressing room. Just as I was about to get into the dressing room, I managed to see through my skirt what was happening. Anna Pavlova was hanging on the door jamb, laughing so hard she could hardly stand up, wiping her eyes. I also saw Mrs. Ratliff holding a handkerchief to her eyes, but she wasn’t smiling. That was the end of the future ballerina of the world! I never have grown. I stopped growing—I think it was from that experience.

Being born at the turn of the century meant before women’s suffrage, the eight hour day, etc. But more important than the outward signs of women’s unrest was the psychological atmosphere of that period.

When I was 12 I came across a book (which I think was by an English writer of the 1890s) which stated that women’s nervous systems were not equal to the strain of ‘mentation.’ That in fact women could never do any meaningful creative work as they didn’t have the capacity for sustained intellectual thought, or any spiritual depths sufficient to create a masterpiece; that the few women who did create works of art (Marie Vigée-Lebrun, Rosa Bonheur, George Sand) were really not true women, and anyway their work was definitely inferior.

This was a profound shock to me—for up to that time I had believed that I was as smart, if not smarter, than any of my boy playmates.

I asked my father if it was true, that women were definitely inferior to men and, bless his heart, he assured me that it was only an old-fashioned idea, that I could be anything or do anything I wanted, providing that one, I had some talent for it and two, I was willing to work single-mindedly enough.

I mention this only to give some idea of the conditioning that girls received as a matter of course: ‘Don’t Try, You Can’t Succeed,’ or the motto that was always quoted, ‘Be good, sweet maid, and let who will be clever.’ Wow!

My mother and father continued the English habit of taking Sunday afternoon walks and looking at other peoples’ gardens. They walked a few blocks above us to Georgia Street and saw this wonderful garden, full of trees completely unknown to them: loquats, kumquats, small bush guavas, and a profusion of flowers. They met the owners, who turned out to be artists.

Anna M. Valentien was a sculptor who had studied with Rodin in Paris. She had come back to America and worked in the Rookwood Pottery, modeling shapes and doing decorations for the pottery. She’d done beautiful large pieces of pottery, with nude figures that looked as if they were swimming in water. She used a matte glaze and shading from cool white down to sea green at the base.

Her husband, whom we always addressed as Mr. Valentien, was a painter and at the time was making a series of paintings of California wild flowers. I was allowed to walk up there and talk to Mrs. Valentien but not bother Mr. Valentien, though I did. Of course, the first time I met them, when I heard they were artists, I piped up and said, “That’s what I’m going to be. I’m going to be an artist.” So they were interested, I guess, because most children don’t say that. She was very kind. She showed me some of her work, some small sculptures she had done. It was just wonderful to know that they were artists and that we were friends with them. That meant a lot to me.

In 1915-1916 the Panama-California Exposition was held in San Diego, to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal. It had a wonderful gallery that exhibited artists’ work from all over the world. I saw three Monets that I’ve never forgotten. One from the hayfield series. Two paintings were facades of churches—the kind that when you got too close, they simply fell away and became dabs of paint. But when you backed off, they suddenly strengthened and tightened and became facades of stone buildings bathed in sunlight. The same process happened with the haystack painting. People thought them very ‘advanced,’ although they had been painted circa 1894!

There were paintings by California artists and some from back East, but I don’t remember the names. I was 14 when I saw what you might call my first international painting. To see what was being done all over the world made a tremendous impression on me.

I was absolutely zapped by the decor Frances Elkins did for the Main Lounge in the Exposition building, exhibiting Women’s Work. She used yard strips of a gorgeous ultramarine blue and an equally brilliant yellow orange sewn lengthwise to make draperies of gigantic stripes. The sofas were upholstered with the same clear glowing blue, with orange footstools. The windows were large and high, so this was a dramatic expanse. The furniture, which I recognized as regular bureaus with drawers, had been silver leafed, then the silver leaf abraded a little to antique them. The other furniture was wicker, alternating either orange or deep blue cushions. Most people said that the clashing colors gave them a headache, so the following year the scheme was changed to something more lady-like.

The other exhibit that thrilled my 14-year-old heart was the facsimile casts of Mayan and Aztec sculpture and bas reliefs. The combination of stylized hair and muscles with factual reality always excited me.

So I was encouraged about art and I made a solemn vow that I would not bother with going to college or the university—I would go to an art school. I heard that there was an art school in San Francisco, so I determined that when I got out of grammar school and through high school, that’s where I would go.

After I entered high school two wonderful things happened. The first was that I found one friend who knew exactly what he was going to do. His name was Marcus Duffield and he wanted to be a journalist, either a foreign correspondent or editor of a big newspaper. And that’s what he did do, too. He became the foreign editor of the New York Herald Tribune.

We would get together and everybody else thought we were having this terrific affair. He’d borrow his father’s car and we’d go out and park some place and then we would talk. Neither one of us would listen to the other. We’d just sit there and talk, talk, talk—each of us saying what we were going to do, because nobody else would believe us. Once in a while we’d stop and he’d tell me why he was taking what courses in high school and what he hoped he’d be able to take in college. I would tell why I wasn’t going to go to college and why I wanted to go to art school.

The second wonderful thing was that the school authorities gave me permission to take a night class in clay modeling, given by our friend Mrs. Valentien. This was exciting because it was my first serious attempt to do something in the Fine Arts.

I wasn’t allowed to ‘take’ art. I majored in Math (my father’s field). This wasn’t any great loss, because all the art students did was make posters urging us to conserve sugar, have victory gardens and buy bonds.

The United States entered World War I in 1917.

Then in 1918, when I was 16, my father was transferred to St. Helens, Oregon, a tiny little place on the Columbia River, just 25 miles from Portland. They were building wooden ships to carry Canadian grain to Great Britain through the Panama Canal. Not only did my father work for the lumber company, he was also a representative of the Canadian government.

By the time we were packed up and ready to move, I had finished my first year of high school. When we finally got up to this little town, there was only one house available—because of the sudden entrance into the War everything had been snapped up. The mills were enlarged. There were shipbuilding docks. We were lucky to get this ancient wooden structure, made with hand-made nails that looked, but really wasn’t, slightly Victorian. It was a siding house with a porch that ran three sides of the house. We wondered at the time why it was available and soon found out when the porch fell off—it was that old.

In 1918 the influenza plague began but St. Helens was so small and isolated—it was mostly men in the mill— that we didn’t have to wear face-masks. And we were right in the town. In the cities they wore face-masks, so we really escaped. There were very few deaths in St. Helens from influenza.

We got there the last day of August and the next day the high school burned down. So for about a week the school didn’t start. Thus I began my sophomore year in high school in a huge improvised room above the town’s only bank, which I think was the Odd Fellows Hall. Think of all four grades of high school students crowded into one large room with an old potbellied stove in the corner. It was ridiculous. And the instruction was terrible. The English studies were pitiful. The math was pitiful. They didn’t have a chemistry class.

I realized that I was losing ground, that unless I went to a better school and learned more I wouldn’t get any kind of education at all—I’d never be able to pass examinations into college or university. So I rebelled.

I told them I was going to take whatever money I had and go back to San Diego, to finish my high school training there—that St. Helens was impossible.

My father understood the situation, of course. We had friends, Mr. and Mrs. Best, who owned an apartment house right near the high school in San Diego. They said that they’d watch over me. So Mother went back to San Diego with me and saw to the apartment. I enrolled again in the Russ High School, the old high school on the hill.

Also at this time I was getting more impatient to go to art school. I just couldn’t stand it. My father was adamant that if I went back to high school I had to get, as he put it, a classical education, that I could always learn to paint later—even though I had never been allowed to take any art courses. So that’s what I was getting. But I was getting very bored with it.

Again I talked to the principal. My grades were high. I took a number of tests and entered as a junior and with a number of senior subjects, for which I had to take examinations. Some of them I passed without ever having been a senior. I worked hard. I had to quit the clay modeling class and devote myself completely to studying to get through two years of high school in one. Which I did.

The scholastic year finally ended. I was through with high school. And if I hadn’t graduated cum laude, at least I received a diploma. Mother came down from Oregon to see me graduate and was a little upset when she found that I had told the school authorities that I would not appear on the platform— they could mail my diploma to my home address in Oregon. I broke that news to Mother, who expected to sit in the audience as a proud parent and watch her daughter receive her reward.

However, she was very game and used to changes of schedules. I said, “Help me pack my trunk, and help me find an apartment in San Francisco.” In those days you had trunks. We packed the trunk and called an expressman, who took the trunk onto his back, carried it down a flight of steps, then dumped it in the back of a truck. Then he drove off to the Southern Pacific station. The trunk was checked at the baggage department, on my ticket, and traveled on the train with me as we took this wonderful trip up to San Francisco.

After we got off the train at Third and Townsend, Mother confessed that she’d scouted ahead before she’d come to San Diego and thought she’d found an apartment for me. We carried our Boston bags, which were the equivalent of the modern flight bag—a small black satchel looking very much like a doctor’s satchel–on the Stockton streetcar and finally got off at Leavenworth. The apartment was just an apartment—I wasn’t thrilled, because it wasn’t a studio, but I accepted it.

After dumping our bags, we immediately went to see the art school. We took a cable car and got off at Mason and California, the corner on Nob Hill where the Mark Hopkins Hotel now stands. Originally the Mark Hopkins mansion was there. After the earthquake the authorities had to dynamite some of these mansions on Nob Hill to stop the fire from coming up because they’d run out of water. The story was that Mrs. Mark Hopkins, all dressed up and carrying a little handbag of jewels, ordered her pair of horses and carriage to come to the door. She stepped in and drove off, leaving everything in the house just as it was. When she got as far as Fillmore Street she heard a couple of dull booms and realized they had dynamited her home.

This dynamited house had nothing left of it except the foundations. On those foundations a temporary building was built (the janitor had to wire together the floor boards so the students wouldn’t fall through to the wine cellars below), and that became housing for the California School of Fine Arts.

I BEGIN MY CAREER IN ART

You walked into the building and a large open room served as a gallery. Since it was summer time, the work completed that spring was on exhibit. Amongst the exhibits of life drawings, sketches, paintings, portraits and still lifes were a series of brilliantly colored designs from the Rudolph Schaeffer Design and Color class. These were tiny compositions maybe five inches by three inches, in gouache, of flattened decorative flowers and leaves. Even today the color would seem prismatic and you can imagine what it looked like in 1920, the tag end of the Brown Mission Furniture Period. I don’t know if Mother was offended by the strength of the colors, but I was stunned by them. I had never seen anything so brilliant, so jewel-like, and the colors were so pure. None of these maroonish reds and sort of cloudy blues. These colors sang! I said to Mother, “I’m signing up for this class. I’ve got to go to Mr. Schaeffer’s class.”

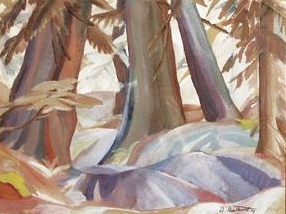

I signed up but there was very little happening in the art school during the summer except for outdoor sketching. My first artistic class was going out sketching with a teacher named Gottardo Piazzoni. I was so thrilled. I was starting my art career.

Mr. Piazzoni led us to the Sausalito Ferry. We went across the Bay—no bridges in those days—and landed in Sausalito. Then we took a little red electric train a few miles into the countryside and got off at a station called Waldo, a beautiful uninhabited spot. As far as you could see there wasn’t a house or anything, only rolling hills going down to an inlet of the Bay.

To our left more rolling hills and live oaks. We crossed a road, which is now, of course, Highway One. There were no fences. We walked up one of the rolling hills and sat down where we had a good view of the Bay and the mountains.

I had never done this in my life and I was in seventh heaven. I had purchased a wooden sketch box with slots to put some canvas boards in, to paint on. I had a selection of student oil paints. I had two oil paint brushes, a bottle of pure rectified spirits of gum turpentine, which doesn’t smell like the stuff they sell nowadays, but it was perfume to me. A little tin cup to put the turpentine in, paint rags and a lead pencil, to start drawing my masterpiece.

I sat near someone so I could see what she was doing. I knew none of these students—this was the first time I’d done anything in an art class—and they didn’t know me, but we got acquainted later on. I didn’t know whom I was watching. She squeezed her paint out; I squeezed my paint out. She put the little tin cup on her wooden pallet; I did the same. I filled it with turpentine. I then started to draw the landscape I saw before me. It wasn’t necessarily good, but I didn’t seem to have any trouble drawing what I saw. I guess I’d just absorbed drawing as a way of doing things. At any rate, I drew what I thought was a fairly simple landscape and started in painting the sky, because the woman I was watching painted the sky first. I just copied her.

After a while Mr. Piazzoni came around. I kept hearing him say something in the distance because we were scattered over the hillside. When he came up close to us, he stood behind me a long time, looking at what I was doing. Finally he said, “Keep eet seemple. Keep eet seemple.” Which seemed to be his watchword because he was a very good painter and he did wonderful simplified paintings of the California hills. As I look back now I had most of the Bay Area depicted in my little 12 inch by 16 inch sketch board. I can see why he told me to “keep eet seemple.”

I sat there and it was heaven on earth. Here I was out of school. I was a painter. I was using oil paint. I was doing a landscape. It was for real. Of course, this euphoria didn’t last very long, but I’ve never forgotten that beautiful morning in the Waldo hills.

In no time it was September and the fall classes started at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Lee F. Randolph was the director of the school and he also taught Life Drawing and Anatomy. There was a couple from New Zealand, E. Spencer Macky, who taught Portrait Painting, and Constance Macky, who taught both Beginning and Advanced Still Life Painting. Gertrude Partington Albright taught Quick Sketch, a Saturday class in Painting, and occasional classes sketching from the moving model. She was a good teacher—a little bit of a thing with glasses and a high voice—but she knew her sketch styles and could really stimulate the students. Our sculpture teacher was Ralph Stackpole, home from Paris via Mexico, and a close friend of Diego Rivera. He taught sculpture in the basement. Harold Von Schmidt taught the Commercial Art classes. Gottardo Piazzoni, of course, then last but not least, my instructor to be, Rudolph Schaeffer. That was the complement of teachers.

There were about two-thirds more men in the school than girls. Part of that was because of returned soldiers, called ‘Federal Board’ students, most of them recovering from shell shock. Nevertheless, it was a man’s business. Ralph Stackpole is reported to have told the girls in his sculpture class (they were cutting direct in stone) that the place where they really belonged was in bed! Women teaching Art was all right. Only male artists who hadn’t really ‘arrived’ taught, so naturally it was okay for women to teach.

I took Color with Schaeffer, Drawing with Randolph, Portrait with Macky, and Advertising Design with Von Schmidt.

My first class was life drawing and I truly realized my abysmal ignorance when I sat down. I found a place where you sat on a little bench with a small drawing board in front of you. I didn’t realize that it was vacant for the simple reason that it was the most difficult pose–the model was reclining and you had a good view of the soles of her feet, which more or less hid the rest of her body. But I didn’t realize that. I couldn’t see what other people were doing. When the model rested I was really too shy to be seen looking at their work. Most of them just indicated things on the paper with charcoal.

Eventually, before the class was over, Mr. Randolph came in to give a little critique. He stood behind me for awhile, then asked, “Are you thinking of making art your profession?” I said, “Oh, yes, sir!” And he said, “Well, look at some of the other students’ work and try to do what they’re doing.” I took that to heart and I did look at their work. I could see that mine was small with a kind of a crocheted, shady edge around it, whereas theirs had large sweeping bold strokes. So I copied that. That was my first morning.

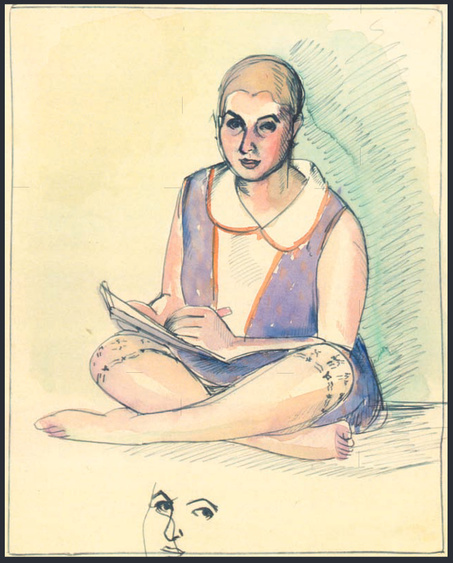

In the afternoon I went to Mr. Macky’s class. This time it was drawing a model—a difficult model because a young child, maybe 12 or 13, was posing. I guess there weren’t child labor laws then. Again, the only vacant space was where I saw him almost in profile, against a bright window, so mostly it was a matter of shading the whole head and ear and shoulder in darkness.

Mr. Macky, in his nice New Zealand voice and accent, was explaining something. I thought he was talking about the plates in the head. I couldn’t imagine what it was. Finally, when he stopped talking and we started drawing, I got up my courage and spoke to the person next to me. “What did he mean, saying about plates?”

“Plates?” she said. “Planes, you dummy, planes of the head.” Then she made the same gestures Mr. Macky had made, with her hands flat on each side of the temples, then kind of curving them across—and I realized what he was talking about.